p.407: FOUNDING OF

Appendix V

FOUNDING OF LONDON AS "TRI-NOVANT" OR "

BY KING BRUTUS-THE-TROJAN, ABOUT 1100 B.C.

It is not surprising that King

Brutus-the-Trojan should have named his

"Skirting

That Helenus, Priam's son o'er Greeks

Bore sway, succeeding to the throne and bed

Of Pyrrhus [see

NOTE] . . . Pyrrhus dead,

Part of his realm to Helenus

demis'd,

Who Chaonia's plain by

title new

'Troy' Chaon called,

and built him walls

And ramparts on the steep whose names remind

Of Pergamus

and

I traced the town, the miniature of

Its yellow shrunken stream, its fort surnamed

'Of Pergamus.' "

{NOTE on "Chaonia" above: The N.E. district of Epirus bordered by the Thyamis river. Virgil, by his use

of the district name "Chaon" and "

{NOTE on Pyrrhus above: Pyrrhus was son of Achilles, and consort of Andromache, wife of Hector, who was carried off by Achilles.}

This clearly shows that the

Trojan colonists were in the habit of consciously and deliberately bestowing

their treasured old Trojan names upon their new colonies, with the avowed

object of "reminding" them of the old homeland of their Aryan

ancestors. Besides this one, another new

{"

The name "Tri-Novantum" could

easily, as Geoffrey states, be "a corruption of

the original word," for the city-name which was imposed by Brutus. That

original word, which Geoffrey does not supply, may be presumed to have

approximated the Gothic "Troia-Ny"

or "Troia-

p.408: PHOENICIAN ORIGIN OF BRITONS & SCOTS

Nyendi";

{"Troia" was the old Greek

name for the old capital city of the Trojans and that identical name for it is

used in the Norse sagas of the thirteenth century (V.I.D., 642); and Ny and Niuiis are

the Gothic originals of the modern English "New" in the Eddas and in Ulfilas' Gospel

translations, corresponding to the Greek Neos,

the Sanskrit Nava and Latin Novus.}

and the "Tri-Novantes" of Caesar are called "Tri-Noantes" by Ptolemy and Tacitus, {Tacitus, Annals, 14, 31.} "Troia," the old Greek and Gothic name for the capital city of the Trojans could become "Tri" in British dialect, as seen in the Old English form of the word "Trifle" being spelt "Trofle," {Piers the Plowman's Crede, 352; Morte Arthure, ed. Brock, 2932.} and "Tryst" is a variant of "Trust." Indeed, the Gothic form of "Troia-Ny" for this "Tri-Novantum" title of early London appears to be preserved in a Norse Edda which mentions "Troe-Noey" along with "Hedins-eyio " or Edin-burgh, {Edinburgh was already called "Fort Edin" or "Fort Eden" (Dun-Edin or Dun-Eden) before the advent of the Anglo-Saxons, see S.C.P., cxlii and 10.} as furnishing a contingent fleet of "long-headed ships" for raiding their joint enemy, the Huns. {"Helga-kvida Hundings Bana," see Edda. (N) 130, and V.P., 1, 134.}

As regards "Tri-Novantum" as a traditional name for early "London," it is remarkable that no modern writer, nor even Geoffrey or Nennius, appears hitherto to have equated that name to the well-known historical title of "Tri-Novantes" for the pre-Roman British people described by Caesar as occupying the Essex or north bank of the Thames estuary, including obviously the site of London city.

Caesar nowhere mentions the name

The reason why Caesar did not mention "Tri-Novantum" city, or "London," appears to be because he obviously did not pass through that city; and he was not in the habit of mentioning places unnecessarily in his very laconic journal; and he does not even mention the names of the place or places where he landed and re-embarked on his two expeditions, nor the name of Cassivellaunus' stronghold, although it was the most important place which he stormed, and described by Caesar as "admirably fortified," and the culminating place of victory in his British war--a fort which has been fairly well identified with Verulam at St. Albans.

Caesar's avoidance of the capital city of the Tri-Novantes,

or

When Caesar, with his veteran

army of 30,000 infantry, besides cavalry, after driving back Cassivellaunus and his raw confederate forces from

p.409: FOUNDING OF

only and

difficult ford, which, on good evidence, is placed at Brent-ford opposite

{One of the lowest, or the very lowest, fords over the

despite

the desperate resistance of the enemy who had planted sharp stakes in the river

and along the bank, Cassivellaunus, despairing of

success in a pitched battle with Caesar's invincible legions, significantly

resorted to the same tactics as ascribed to Brutus in

But on this sudden disappearance of Cassivellaunus' main force at Brentford, the Tri-Novantes, Caesar tells us, were the first Britons to come to his camp (presumably at Brentford) and offer submission and beg protection for Mandubracius against Cassivellaunus. Caesar demanded from them forty hostages for their good faith and corn for his army, and he notes, "They promptly obeyed these commands, sending the hostages to the number required and also the grain; whereupon the Tri-Novantes were granted protection and immunity from all injury on the part of the legions." {Ib., 5, 8.} Thereupon the confederated tribes, and even part of Cassivellaunus' own tribe of Cassis, following the lead of the Tri-Novantes, deserted from Cassivellaunus and submitted to Caesar, presumably won over by the latter through the agency of Mandubracius and by Commius, another exiled Gaulish Briton prince, who also was accompanying Caesar and utilized by him to communicate with the Britons, obviously for the notorious Roman policy of weakening their antagonists by dividing them--"Divide et impera."

Having thus isolated the heroic Cassivellaunus from his confederated Briton chiefs, Caesar promptly pursued him to his stronghold at Verulam--which was almost due north of Brentford and by a good road, in great part the old "Watling Street" which by its name betrays its Gothic Briton origin {A writer of the fourteenth century says Watling Street crossed the Thames to the west of Westminster. See H.A.B., 705.} --and there forced him to surrender, and he eagerly patched up a peace with him, as we learn from the contemporary letters of Cicero, stipulating that Cassivellaunus would not invade the land of the Tri-Novantes, and he immediately hastened back to Gaul to quell the serious insurrections there, and disheartened, as the contemporary Roman writers relate, at the final failure of his attempt to conquer Britain. In his hurried pursuit of Cassivellaunus from Brentford to Verulam and his precipitate retreat to the port of his re-embarkation, in a campaign which lasted only a few weeks, it is clear that Caesar did not enter the capital city of the Tri-Novantes (Tri-Novantum or "London") at all, especially as he was debarred from so doing by his promise to prevent his legions from injuring or molesting in any way the Tri-Novantes, who had so largely contributed to the defeat of Cassivellaunus.

Caesar's account of these events is generally confirmed by the indigenous

p.410: PHOENICIAN ORIGIN OF BRITONS & SCOTS

account of his invasion preserved in the British Chronicles of Geoffrey, {G.C., 3, 20.} which record the real name of "Mandubracius" as "Androgeus"--that is also the form of his name preserved by Bede, {B.H.E., 1, 2.} of which "Mandubracius" is evidently a Roman corruption--and the real circumstances of the flight of that "Duke of Tri-Novantum," and his subordination to Cassivellaunus, the brother of that duke's father, King Lud of Tri-Novantum city, are therein fully recorded; also the fact that Cassivellaunus had magnanimously gifted the city of Tri-Novantum or Lud-Dun ("London") to that renegade, "the betrayer of his country," who had aided Caesar with his own levies.

The remote prehistoric antiquity of the site of London, moreover, is evidenced by the numerous archaeological remains found there, not only of the New Stone and Early Bronze Ages, but even of the Old Stone Age, thus indicating that it was already a Pictish settlement at the epoch when Brutus selected it for the site of his new capital of "New Troy."

The later name of "

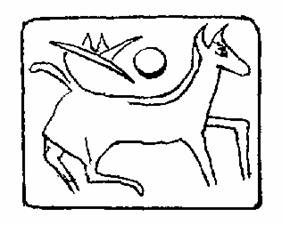

FIG. 76.--Archaic Hittite Sun Horse with Sun's disc and (?) Wings.

From seal found at

Caesarea in

(After Chantre

C.M.C. Fig. 141)

It is carved in serpentine

and pierced behind for attachment. The object above the

galloping horse, behind the disc, is

supposed by M.C. to be a javelin.