[pp. 407-410]

V

FOUNDING OF LONDON AS

"TRI-NOVANT" OR "NEW TROY"

BY KING BRUTUS-THE-TROJAN, ABOUT 1100

B.C.

It

is not surprising that King Brutus-the-Trojan should have named his new city on

the Thames in the new land of his adoption "New Troy," especially as

the city on the old river Thyamis in Epirus, whence he came was also named

"Troy." {It is named "Ilium" on later maps (see D.A.A., No.

11), that is the Latin spelling of Ilion, Homer's usual title for

"Troy."} The

naming of this new "Troy" in Epirus by Helenus, the fugitive son of

King Priam of Troy, is described by Ovid {Metamorphoses, 13, 721.} and Virgil. The latter says {Æneid, 3, 295, etc.}:—

"Skirting

Epirus' coast, Chaonia's [see NOTE] port . . .

That Helenus,

Priam's son o'er Greeks

Bore sway,

succeeding to the throne and bed

Of Pyrrhus [see

NOTE] . . . Pyrrhus dead,

Part of his

realm to Helenus demis'd,

Who Chaonia's

plain by title new

'Troy' Chaon

called, and built him walls

And ramparts on

the steep whose names remind

Of Pergamus and

Troy. . . . In pensive thought

I traced the

town, the miniature of Troy,

Its yellow

shrunken stream, its fort surnamed

'Of Pergamus.'

"

{NOTE on "Chaonia" above: The N.E. district of Epirus bordered by the

Thyamis river. Virgil, by his use of the district name "Chaon" and

"Xanthus" for the river, which I have rendered "yellow,"

presumably locates the city on the latter river and thus identifies this Troy

with "Phœnice" there.}

{NOTE on Pyrrhus above: Pyrrhus was son of Achilles, and consort of

Andromache, wife of Hector, who was carried off by Achilles.}

This

clearly shows that the Trojan colonists were in the habit of consciously and

deliberately bestowing their treasured old Trojan names upon their new

colonies, with the avowed object of "reminding" them of the old

homeland of their Aryan ancestors. Besides this one, another new Troy is

reported to have been founded by Æneas in the Tiber Valley {Livy, 1, 1,

3.} and still another by a Trojan colony near Memphis in Egypt. {S., 808; 17,

1, 34.} And even the famous Troy of the Homeric epic appears to have been

called "New Troy" in distinction presumably to the Old Troy

underlying that site. {The "Nun Ilion" of Strabo, the so-called

"Novum Ilium" of S.I., 19 and 38.} This old Trojan habit of naming some of their chief new

colonial cities is analogous to that by which in modern times New York derived

its name.

{"Troy"

or Troia was named after Tros, the founder of the old city. New York was

first named New Amsterdam (and thus in series with New Troy) when

founded by the Dutch in 1624; but when seized in 1664 by the British, it was

granted by Charles II. to his brother the Duke of York, after whom it received

its present name; and that name was derived from the old ducal city state in

Britain, which Briton city, in its turn, as recorded by Geoffrey's Chronicle,

was named after a descendant of Brutus.}

The name "Tri-Novantum" could

easily, as Geoffrey states, be "a corruption of the original word,"

for the city-name which was imposed by Brutus. That original word, which

Geoffrey does not supply, may be presumed to have approximated the Gothic

"Troia-Ny" or "Troia-Nyendi";

{"Troia" was the old

Greek name for the old capital city of the Trojans and that identical name for

it is used in the Norse sagas of the thirteenth century (V.I.D., 642); and Ny

and Niuiis are the Gothic originals of the modern English

"New" in the Eddas and in Ulfilas' Gospel translations, corresponding

to the Greek Neos, the Sanskrit Nava and Latin Novus.}

and

the "Tri-Novantes" of Cæsar are called "Tri-Noantes"

by Ptolemy and Tacitus, {Tacitus, Annals, 14, 31.} "Troia,"

the old Greek and Gothic name for the capital city of the Trojans could become

"Tri" in British dialect, as seen in the Old English form of

the word "Trifle" being spelt "Trofle," {Piers the

Plowman's Crede, 352; Morte Arthure, ed. Brock, 2932.} and "Tryst" is a variant of

"Trust." Indeed, the Gothic form of "Troia-Ny" for

this "Tri-Novantum" title of early London appears to be preserved in

a Norse Edda which mentions "Troe-Noey" along with "Hedins-eyio

" or Edin-burgh, {Edinburgh was already called "Fort Edin" or

"Fort Eden" (Dun-Edin or Dun-Eden) before the advent of the

Anglo-Saxons, see S.C.P., cxlii and 10.}

as furnishing a contingent fleet of "long-headed ships" for raiding

their joint enemy, the Huns. {"Helga-kvida Hundings Bana," see Edda.

(N) 130, and V.P., 1, 134.}

As regards "Tri-Novantum" as a

traditional name for early "London," it is remarkable that no modern writer,

nor even Geoffrey or Nennius, appears hitherto to have equated that name to the

well-known historical title of "Tri-Novantes" for the

pre-Roman British people described by Cæsar as occupying the Essex or north

bank of the Thames estuary, including obviously the site of London city.

Cæsar nowhere mentions the name London,

for the obvious reason to be seen presently. The name "London" for

the British "Lud-dun" or "Fort Lud" of the Cymric

records is first mentioned in Roman history by Tacitus in 61 A.D., who

described it as "the most celebrated centre of busy commerce," {Annals,

14, 33, 1.} and he refers to it in such a way as to imply its time-immemorial

existence as a city. And the historian Ammianus Marcellinus, of the fourth

century, calls London (Londinium) "an ancient town towards which Cæsar

marched," {A.M.H., 27, 8, 7.} thus clearly implying that the ancient city

was in existence in Cæsar's day.

The reason why Cæsar did not mention

"Tri-Novantum" city, or "London," appears to be because he

obviously did not pass through that city; and he was not in the habit of

mentioning places unnecessarily in his very laconic journal; and he does not

even mention the names of the place or places where he landed and re-embarked

on his two expeditions, nor the name of Cassivellaunus' stronghold, although it

was the most important place which he stormed, and described by Cæsar as

"admirably fortified," and the culminating place of victory in his

British war—a fort which has been fairly well identified with Verulam at St.

Albans.

Cæsar's avoidance of the capital city of

the Tri-Novantes, or London, in his hurried brief campaign is apparent, it

seems to me, from his own narrative. He states that at his second invasion of

the S.E. corner of Britain, the Tri-Novantes were at war with Cassivellaunus,

his chief enemy, and the paramount king of the Britons and leader of the

confederated tribes, {D.B.G., 5, 5.} and whose personal territory extended

northwards from the north bank of the Thames, excluding the province of the

Tri-Novantes, which comprised the petty kingdom now known as the eastern

portion of Middlesex and Essex. Cassivellaunus, according to Cæsar's

information, had slain the king of the Tri-Novantes some time previously, and

the son of the latter, Mandubracius, had fled for protection and assistance to

Cæsar in Gaul, and was accompanying Cæsar in his invasion and supplying him

with auxiliary troops and information, so that he is called in the Welsh Triads

"the betrayer of his country."

When

Cæsar, with his veteran army of 30,000 infantry, besides cavalry, after driving

back Cassivellaunus and his raw confederate forces from Kent to the Thames,

forced the passage of the Thames at its lowest only and difficult ford, which,

on good evidence, is placed at Brent-ford opposite Kew,

{One of the

lowest, or the very lowest, fords over the Thames was formerly at Brentford,

and it was "difficult," on account of its depth and the tides. Mr. M.

Sharpe found from the Thames Conservancy that a line of stakes, of which some

still remain "for about 400 yards below Isleworth Ferry," extended 45

years ago for about a mile up the river from "Old England," opposite

the mouth of the Brent, and that "no other ancient stakes have been

discovered in the lower river during dredging operations" (Bregant-forde

and the Hanweal, 1904, 1, 22-7). The name "Brentford" itself,

however, did not refer to this ford over the Thames, but to the small ford over

the Brent at its junction with the Thames. And Brentford is about due south of

Verulam by a good road, in part the "Watling" Road.}

despite

the desperate resistance of the enemy who had planted sharp stakes in the river

and along the bank, Cassivellaunus, despairing of success in a pitched battle

with Cæsar's invincible legions, significantly resorted to the same tactics as

ascribed to Brutus in Epirus, when attacked by the overwhelming forces of

Pandrasus. He disbanded the greater part of his army, and for guerrilla war

withdrew the people and their cattle into the recesses of the impenetrable

woods, to which he retired himself with a small contingent—Cæsar says he

retained "only about four thousand charioteers"—with which he

harassed the detached foraging parties of the enemy and cut off stragglers,

causing Cæsar to admit that "Cassivellaunus engaged our cavalry to their

great peril and by the terror which he thus inspired prevented them from

moving far afield." {D.B.G., 5, 8.}

But

on this sudden disappearance of Cassivellaunus' main force at Brentford, the

Tri-Novantes, Cæsar tells us, were the first Britons to come to his camp

(presumably at Brentford) and offer submission and beg protection for

Mandubracius against Cassivellaunus. Cæsar demanded from them forty hostages

for their good faith and corn for his army, and he notes, "They promptly

obeyed these commands, sending the hostages to the number required and also the

grain; whereupon the Tri-Novantes were granted protection and immunity from

all injury on the part of the legions." {Ib., 5, 8.} Thereupon

the confederated tribes, and even part of Cassivellaunus' own tribe of Cassis,

following the lead of the Tri-Novantes, deserted from Cassivellaunus and

submitted to Cæsar, presumably won over by the latter through the agency of

Mandubracius and by Commius, another exiled Gaulish Briton prince, who also was

accompanying Cæsar and utilized by him to communicate with the Britons,

obviously for the notorious Roman policy of weakening their antagonists by

dividing them—"Divide et impera."

Having

thus isolated the heroic Cassivellaunus from his confederated Briton chiefs,

Cæsar promptly pursued him to his stronghold at Verulam—which was almost due

north of Brentford and by a good road, in great part the old "Watling

Street" which by its name betrays its Gothic Briton origin {A writer of

the fourteenth century says Watling Street crossed the Thames to the west

of Westminster. See H.A.B., 705.} —and there forced him to surrender, and he

eagerly patched up a peace with him, as we learn from the contemporary letters

of Cicero, stipulating that Cassivellaunus would not invade the land of the

Tri-Novantes, and he immediately hastened back to Gaul to quell the serious

insurrections there, and disheartened, as the contemporary Roman writers

relate, at the final failure of his attempt to conquer Britain. In his hurried

pursuit of Cassivellaunus from Brentford to Verulam and his precipitate retreat

to the port of his re-embarkation, in a campaign which lasted only a few weeks,

it is clear that Cæsar did not enter the capital city of the Tri-Novantes (Tri-Novantum

or "London") at all, especially as he was debarred from so doing by

his promise to prevent his legions from injuring or molesting in any way the

Tri-Novantes, who had so largely contributed to the defeat of Cassivellaunus.

Cæsar's

account of these events is generally confirmed by the indigenous account of his

invasion preserved in the British Chronicles of Geoffrey, {G.C., 3, 20.} which record the real name of

"Mandubracius" as "Androgeus"—that is also the form of his

name preserved by Bede, {B.H.E., 1, 2.} of which "Mandubracius" is evidently a Roman

corruption—and the real circumstances of the flight of that "Duke of

Tri-Novantum," and his subordination to Cassivellaunus, the brother of

that duke's father, King Lud of Tri-Novantum city, are therein fully recorded;

also the fact that Cassivellaunus had magnanimously gifted the city of

Tri-Novantum or Lud-Dun ("London") to that renegade, "the

betrayer of his country," who had aided Cæsar with his own levies.

The remote prehistoric antiquity of the

site of London, moreover, is evidenced by the numerous archaeological remains

found there, not only of the New Stone and Early Bronze Ages, but even of the

Old Stone Age, thus indicating that it was already a Pictish settlement at the

epoch when Brutus selected it for the site of his new capital of "New

Troy."

The

later name of "London" for "New Troy" appears to be a

corruption of the late Briton name of "Lud-Dun" or "Lud's

Fort," applied to it by Lud, the elder brother of Cassivellaunus, as

recorded in the Chronicles; and "Caer-Lud" or "Lud's Fort"

is still the Welsh name for London. This later Briton name for it is seen to

survive in the modern names "Lud-gate Hill" and "Lud-gate

Circus," which indicate that the old city or its citadel centred about St.

Paul's; and that a chief gate appears to have been at Ludgate Circus on the

banks of the old river Flete, the modern "Fleet," which in medieval

times was a considerable navigable creek bordered by extensive marshes. {C.B., 1, 80.} That creek obviously derived its name

from its use as the old harbour of the naval fleet of those days—the "long

headed ships of Trœ-Nœy" of the Norse Edda afore mentioned. That

name "Fleet" is now seen to be derived from the Eddic Gothic Fliota,

"to float, flit or be fleet," {V.D., 161.} and secondarily floti, "a ship or fleet or

number of ships," {Ib., 161.} and cognate with the Greek ploion, "a hull or

ship." The corruption of "Lud-dun" into "London"

appears to have been due to the later Romans, who called it

"Londinium." Yet it is noteworthy that the o in the modern

city name is still pronounced with its old u sound.

London thus appears to have been founded as the capital city of the Brito-Phœnicians or Early Britons many centuries before Athens and the rise of historic Greece; and three and a half centuries before the traditional foundation of Rome.

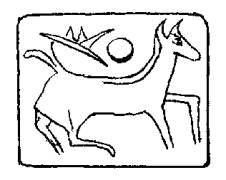

FIG. 76.—Archaic Hittite Sun Horse with

Sun's disc and (?) Wings.

From seal found at Cæsarea in Cappadocia.

(After

Chantre C.M.C. Fig. 141)

It

is carved in serpentine and pierced behind for attachment. The object above the

galloping

horse, behind the disc, is supposed by M.C. to be a javelin.

KEY TO SOURCES

used in this appendix:

D.A.A. Dent's

Atlas of Ancient Classic Geography.

S. Strabo's

Geographia.

S.I. Ilios.

H. Schliemann. 1880.

V.I.D. [=V.D.?]

S.C.P. Chronicles

of Picts and Scots. W. F. Skene. 1867.

V.P. Vishnu

Parana, trans. by H. H. Wilson, ed. F. Hall. 1864.

A.M.H. Roman

History of Ammianus Marcellinus, Bohn's ed.

D.B.G. Cæsar's

De Bello Gallico.

H.A.B. Ancient

Briton and Invasion of Julius Cæsar. T. R. Holmes. 1907.

G.C. Hist.

Britonium. Geoffrey of Monmouth, tr. by A. Thompson, 1718, in "Old English

Chronicles" by J. A. Giles. 1882.

B.H.E. Hist.

Ecclesiast. Gentis Anglorum. Bede ed. 1631.

C.B. Britannia.

W. Camden; ed. R. Gough, 2nd ed. 1806.

V.D. Icelandic-English

Dictionary. G. Vigfusson. 1874.