This electronic edition scanned and edited by http://www.jrbooksonline.com July 2006

THE BROADWAY TRAVELLERS

EDITED

BY SIR E.

H A N S

S T A D E N

THE TRUE HISTORY

OF HIS CAPTIVITY

1557

Translated

and edited by Malcolm Letts

with an Introduction and Notes

Published

by

GEORGE

ROUTEDGE &

BROADWAY HOUSE,

First

published in the Broadway Travellers, 1928

[orig. printing notice]

PRINTED IN

BILLING

PREFACE

The first translator, Mr. A. Tootal, worked from

the

I desire to express my thanks to the Council of the Hakluyt Society for the permission indicated above; to the Royal Geographical Society, and particularly to its Librarian, Mr. Ed. Heawood, for advice and assistance; to Professor R. Häpke of Marburg University for information concerning Dr. Dryander, the learned Marburg professor who first introduced Hans Staden to the world; to the publishers for the willingness with which they acceded to my request for the reproduction of all the woodcuts; and to my wife for much help in checking and proof-reading.

Staden's spelling of proper names is most erratic.

I have not attempted to correct him except in the case of well-known places

such as

The first edition of the book is very scarce. I have worked on a beautiful

copy in the Grenville Library at the

MALCOLM LETTS.

Easter, 1928.

CONTENTS

[orig]

PAGES

PREFACE v

INTRODUCTION 1

NOTE TO INTRODUCTION 15

DR. DRYANDER'S INTRODUCTION 21

PART I

CHAPTER

[The voyage to

CHAPTER TWO

My first voyage from Lisbon in Portugal 35–38

CHAPTER THREE

How the

savages of the place called Prannenbucke (Pernambuco) rebelled and strove to expel the Portuguese

from their settlement

39

CHAPTER FOUR

The nature of our defences

and how they fought against us 39–41

CHAPTER FIVE

How we sailed

away from Prannenbucke (Pernambuco) to a country called Buttugaris

and engaged a French vessel 42–44

CHAPTER SIX

My next voyage from Seville in Spain to

America 44–45

CHAPTER SEVEN

In what

manner we reached

vii

CHAPTER EIGHT

In what manner we left the harbour to seek the country for which we were bound 48

CHAPTER NINE

How certain among us set of in a boat to inspect the harbour, and how we found a crucifix handing on a rock 49–51

CHAPTER

In what manner I was dispatched with a boat full of savages to our ship 52–53

CHAPTER ELEVEN

How the other ship arrived, in which was the chief pilot, and which we had loft at sea 53

CHAPTER TWELVE

How we took counsel and sailed for the Portuguese colony of Sancte Vincente, where we intended to freight another ship with which to complete our voyage; how we suffered shipwreck in a storm, not knowing how far we were from Sancte Vincente 54–56

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

How we learnt in what savage country we had been shipwrecked 56–57

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

The situation of Sancte

Vincente 57–58

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

How the place is named in which the enemy is chiefly gathered together, and how it is situated 58–59

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

In what manner the Portuguese rebuilt Brikioka, and later constructed a fort in the island of Sanct Maro 59–61

viii

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

How and for what reasons it was necessary to keep watch for the enemy at one season of the year more than at other times 61

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

My capture by the savages and how it occurred 62–64

CHAPTER NINETEEN

How my people came out when the savages were carrying me away, intending to recapture me, and how they fought with the savages 64–66

CHAPTER TWENTY

In what manner my captors returned to their own country 66–69

CHAPTER TWENTY-

How they dealt with me on the day on which they brought me to their dwellings 69–70

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

How my two captors came to me and told me that they had presented me to one of their friends, who would keep me and slay me when I was to be eaten 71–72

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

How they danced with me before the huts in which their idols Tammerka had been set up 73

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

How, after they had danced, they brought me home to Ipperu Wasu who was to kill me 74

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

How my captors made angry complaint that the Portuguese had slain their father, which deed they desired to avenge on me 75–76

ix

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

How a Frenchman who had been left among the savages came to see me and bade them eat me, saying that I was truly a Portuguese 76–77

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

How I suffered greatly from toothache 77

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

In what manner they brought me to their chief ruler, King Konyan Bebe, and how they dealt with me there 78–81

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

How the Tupin Ikins came with twenty-five canoes, as I had predicted, to the king, intending to attack the huts where I was kept 81–82

CHAPTER THIRTY

In what

manner the chiefs assembled in the moonlight 82–83

CHAPTER THIRTY-

How the

Tupin Ikins burnt another village

called Mambukabe 84

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

How a ship came from Brikioka enquiring for me, and of the brief report which was given 84–85

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

How the brother of the king Jeppipo Wasu returned from Mambukabe with the news that his brother and mother, and all the company had fallen sick, and entreated me to procure my God to make them well again 85–86

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

In what manner the sick king Jeppipo Wasu returned home 86–89

x

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

How the Frenchman returned who had told the savages to eat me, and how I begged him to take me away, but my matters would not suffer me to go 89–91

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

Of the manner in which the savages ate a prisoner and carried me to the feast 91–93

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN

What happened on the homeward journey after the man had been eaten 93–94

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT

How once

more a ship was sent after me by the Portuguese 95–98

CHAPTER THIRTY-NINE

How a slave, who had perpetually defamed me and desired to have me killed, was himself killed and eaten in my presence 98–101

CHAPTER

How a French

ship arrived to trade with the savages for cotton and

CHAPTER

How the savages went forth to war taking me with them, and what befell me on the way 103–107

CHAPTER

How the prisoners were disposed of on the

return voyage 107–110

CHAPTER

How they danced in the camp on the following day with their enemies 110–111

xi

CHAPTER

How the French ship, to which the savages had promised to bring me, was still there when they returned from the war 112

CHAPTER

How they ate George Ferrero, the Portuguese captain's son, and the first of the two roasted Christians 112–113

CHAPTER

How Almighty God worked a wonder 113–114

CHAPTER

How I went fishing one evening with two savages, and God worked another wonder with rain and storm 114–115

CHAPTER

How the savages ate the second roasted Christian, called Hieronymus 115–116

CHAPTER

How they carried me to be given away 116–117

CHAPTER FIFTY

How the savages of this place reported to me that the French ship had sailed away again 117

CHAPTER FIFTY-

How shortly after I had been given away another ship arrived from France, the Catherine of Vattavilla, which through God's providence was able to buy me, and of the manner in which this fell out 117–120

CHAPTER FIFTY-TWO

The name of the ship's captain, from whence the ship came, and what happened before we left harbour, and the manner of our return to France 120–122

xii

CHAPTER FIFTY-THREE

How at

My prayer to the Lord God when I was in the hands of the savages who threatened to eat me 124–125

PART II

CHAPTER

The manner of the voyage from Portugal to Rio de Janeiro in America 128

CHAPTER TWO

The situation of the land called

CHAPTER THREE

Concerning a great range of mountains which is

in the Country 129–131

CHAPTER FOUR

Concerning the dwellings of the Tupin Inba, whose prisoner I was 131–133

CHAPTER FIVE

In what manner they make fire 133–134

CHAPTER SIX

Of their manner of sleeping 134

CHAPTER SEVEN

Of their skill in shooting beads and fish with arrows 134–136

CHAPTER EIGHT

Of the appearance of the people 136

CHAPTER NINE

How

they cut and hew without axes, knives and scissors 136–137

CHAPTER

Concerning their bread and the names of their fruit; how they plant them and prepare them to be eaten 137–139

CHAPTER ELEVEN

How they prepare their food 139–140

CHAPTER TWELVE

Concerning their government by chiefs, and their laws 140

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

How

they bake the pots and vessels which they use 140–141

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

How they concoct their drinks and make themselves drunk therewith, and the manner of their drinking 141–142

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Of the manner in which the men adorn and paint themselves, and of their names 142–144

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Concerning the adornment of the women 145

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

How they first name a child 145–146

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

How many wives a man has, and his manner of dealing with them 146

xiv

CHAPTER NINETEEN

Of their betrothals 147

CHAPTER TWENTY

Of their possessions 147

CHAPTER TWENTY-

What is their greatest honour 148

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

Of their beliefs 148–150

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

How they turn the women into soothsayers 150–151

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

Concerning their canoes

151

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

Why one enemy eats another

152

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

Of their plan of campaign when they set out to invade their enemy's country 152–153

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

Concerning their

weapons 154

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

Of their manner of killing and eating their enemies. Of the instrument with which they kill them, and the rites which follow 155–163

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

Concerning certain animals in the country 164

xv

CHAPTER THIRTY

[Certain animals] 165–166

CHAPTER THIRTY-

Concerning a small insect, like a flea, which the natives call Attun 166

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

Concerning a kind of bat which at night bites the toes and foreheads of the people when they are asleep 166

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

Concerning

the bees of the country 167

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

Concerning

the birds of the country 167

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

An account

of certain trees in the country 168

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

Concerning the growth of the cotton plant, and the Brazilian pepper plant, and of certain other roots which the savages plant for food 168

The concluding address. Hans Staden wishes the reader mercy and peace in God's name 169–171

NOTES 173–183

INDEX 185–191

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Map to illustrate the two

voyages

at end

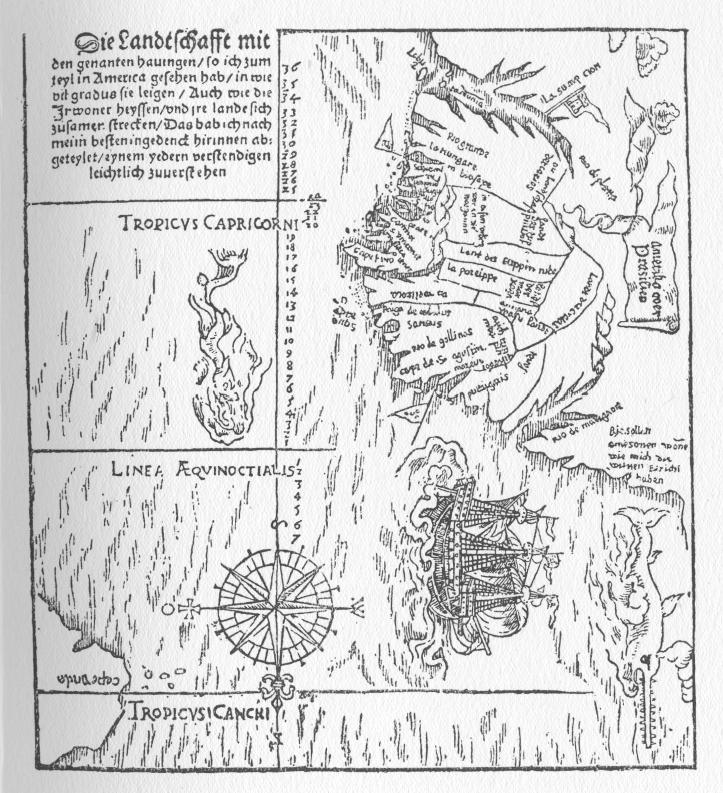

Hans Staden's map p. 31

Map showing

the islands of San Vincente and Santo Amaro p. 58

xvi

DESCRIPTIVE LIST OF THE WOODCUTS

THE woodcuts which adorn the

first edition of the book and which are here reproduced are very remarkable,

even if they are not quite up to the standard of mid-sixteenth-century work in

general. They must have been executed under Hans Staden's

personal supervision, and he figures in nearly all of them. He is easily

recognized by his beard, and in many of them his hands are raised in prayer.

The artist seems to have placed his initials, D.H., on the ship's flag in the

illustration on p. 33, but it has not been possible to identify him. The lower

of the two woodcuts on p. 163 has the initials H.S., but these are probably

inserted to identify Hans Staden who stands

immediately below them. Counting the ornaments on pp. 18 and 125, but excluding

the map, there are fifty-six woodcuts, namely thirty-three in Part I. and

twenty-three in Part II. Of these three are duplicated. The woodcuts appear

only in the

Page 31. Hans Staden's

map is interesting as an early attempt at cartography, but not very helpful.

The title reads: "The country with the harbours

which in part I saw in

xvii

DESCRIPTIVE LIST OF THE WOODCUTS

inhabitants, how they are called, and the manner in which their countries adjoin each other. This I have contrived according to the best of my ability for the better understanding of each judicious reader." There is an interesting note at the right-hand corner of the map by the tail of the sword-fish: "Here Amazons are said to dwell, as I was told by the savages." The legend was well established by the sixteenth century. Another German, Ulrich Schmidel (1534-54), went off in search of the Amazons, and Purchas adds a characteristic note: "The Amazons are still further off. I doubt beyond the region of Truth." For the Stories of the Amazons in S. America see G. Friederici, Die Amazonen Amerikas, Leipzig, 1910; Southey, History of Brazil, 1810, I, p. 604; and generally Archiv für Anthropologie, V (1872), pp. 220-225.

Pages 33, 35. Two drawings of ships.

Page 36. Shows Cape de Gell (Arzilla) and the capture of the boat.

Page 38. The ship surrounded by fish as described on p. 37.

Page 41. An interesting view of Garasu with some business-like cannon inside the enclosure. Below is the food-party on its way to Itamaraccá, while the attackers are throwing down trees across the channel.

Page 42. The harbour and settlement of Buttugaris, and the fight with the French ship.

Page 44. See woodcut on p. 35.

Page 46. The haven of Supraway (Superaqui).

Page 49. The island and

Page 56. The shipwreck,

with Hans Staden reaching shore on a kind of raft.

This woodcut (compare with that at p. 65) gives an excellent idea of the

country described in the book. On the mainland is Brikioka

(Bertioga), and adjoining, in

Page 63. Hans is captured on the

Page 65. The attempted

recapture. Hans is seen in a boat holding a gun. At the extreme corner

of the

Page 67. Hans lying on the ground praying.

Page 68. Hans beseeching God to drive away the storm.

xviii

DESCRIPTIVE LIST OF THE WOODCUTS

Page 72. Inside the settlement at Uwattibi (Ubatúba). Hans is being shaved.

Page 73. Hans with head-dress and rattles beating time while the women dance.

Page 80. Hans with his legs tied together. By him is the king's son wearing the Enduap (p. 144).

Page 82. The attack on the settlement.

Page 83. Hans praying while the angry moon looks down on the huts. His prayer is written above his head: "O Lord God, rescue me from this danger and bring it to a peaceful end." This woodcut is interesting as it shows the savages smoking. There is no reference to this custom in the text, but other travellers speak of it. See, e.g., Purchas (reprint), XVI, pp. 425-6.

Page 87. Hans preparing to lay hands on the sick. The victims of the pestilence are being buried in holes by the huts.

Page 96. Hans in the boat speaking with the crew of the Portuguese ship.

Page 100. This shows Hans attempting to bleed the sick slave, the slave being dispatched with the club, and his body being cut up.

Page 102. Hans escapes to the French ship, but is repulsed.

Page 106. The camp at Boywassu Kange.

Page 107. The fight with the Tupinikin.

Page 108. The fate of the prisoners.

Page 111. The other prisoners are paraded in the camp.

Page 113. The miracle of the cross. Women with their children on their backs.

Page 115. The fishing expedition. Hans is seen praying. The storm is shown in the background.

Page 121. The fight in the

Page 122. The homeward voyage.

Page 127. Two chiefs, one with the sacrificial club, the other wearing head-dress and the Enduap (p. 144).

Page 132. The huts and stockade, with heads on the entrance-posts.

Page 133. Making fire.

Page 134. A hammock.

Page 135. Fishing.

Page 138. This is identical with the woodcut on p. 113.

Page 141. Preparing the drink.

Page 143. Lipstones.

Page 144. The ornament of ostrich plumes, called Enduap.

xix

DESCRIPTIVE LIST OF THE WOODCUTS

Page 148. Pots, and the rattle called Tammaraka.

Page 155. This is identical with the woodcut on p. 72.

Page 156. See woodcut on p. 73.

Page 157. The sacrificial club, called Iwera Pemme.

Page 158. Preparations for a cannibal feast.

Page 159. (a) The victim being painted; (b) the club hanging in the hut (p. 157).

Page 160. The victim drinking with his captors.

Page 161. The victim tied with the rope Mussurana (p. 156).

Pages 162, 163. These woodcuts need no comment.

Page 164. A wart-hog.

Page 165. An opossum.

xx

Hans Staden

The

True History

INTRODUCTION

VERY little is known about Hans Staden except the story of his voyages and captivity among

the Tupi Indians of Brazil. He was born at Homberg in

B

encountering heavy weather they reached Pernambuco on

2

INTRODUCTION

considerable exaggeration, at eight thousand men,

and after a fruitless attempt by the attackers to cut off the food supplies and

smoke out a food party with the fumes of burning pepper, the natives withdrew, and

terms were arranged between them and the Portuguese. Hans Staden

then sailed again for

When Hans Staden returned to

3

by the second ship, but the third vessel was never

heard of again. The crews now began to collect provisions for their voyage to

San Vincente, where they found themselves, was

situated on an island of that name formed by an inland tidal channel, sometimes

called the

4

INTRODUCTION

It was the first Portuguese colony in

It is a moving and exciting story. The Tupinambá regarded the Portuguese as their bitterest enemies, fit only when caught to be cooked and eaten. They complained that the Portuguese, when they arrived to trade, had induced the natives to enter their ships and had then seized and enslaved them, or had sold them to their enemies. Hans Staden was carried

5

off to their settlement at Ubatuba, to the south

of San Vincente, his eyebrows were shaved off with a

piece of glass, and soon his beard disappeared as well, and it was obvious that

he was to be killed and eaten. He seems during his two years of enforced

idleness in the

It was at this stage that some doubts as to his nationality began to dawn upon his captors. The colour of his beard (which was red) had already attracted remark, since the Portuguese had mostly black beards, and the savages could not run the risk of eating a Frenchman or even an ally of the French. Then, by a lucky chance, one of his masters fell sick

6

while he was away on an expedition, and sickness seized the whole of his party. There had already been some talk about the man in the moon looking down angrily upon the savages' huts, and now the sick chief sent a messenger to ask the prisoner to tell his God to make him well again. No one can blame Hans Staden for making the most of his opportunities, and he played his cards with caution and skill. He replied that his God was indeed wrath with the chief and his people because they had called him a Portuguese and had threatened to eat him. Nevertheless, he went about laying his hands on the sick, and although his ministrations were not wholly successful, for many of the sufferers died, yet the chief recovered, and Hans Staden's stock began to rise. They told him their dreams. One chief, who on an earlier occasion had partaken so freely of roasted Portuguese that his digestion was permanently impaired, was much perturbed at his terrible nightmares and vowed that he would never touch Portuguese flesh again. Even Hans Staden's great enemy, a chief named Alkindar, on promising to mend his ways, was cured of eye-ache. Then the French trader returned collecting feathers and pepper, and he so far repented of his previous conduct as to tell the savages that Hans was indeed an ally of his people and that they had better let him go. But the Tupinambá were not going to part with their prophet, and the Frenchman departed alone.

It is doubtful if Hans Staden was ever again in danger of death, but he was to witness a good deal of cannibalism. The reader can follow the gruesome details for himself, but the rites and ceremonies observed in connection with the slaying and eating are curious and interesting. The victim was painted and adorned with feathers and his eyebrows were shaved. For a time at least he was well treated. He

7

received a hut and furniture and was provided with a wife. Meanwhile his captors visited him frequently and examined him to see which of his limbs and joints they proposed to claim. His children were reared and might or might not suffer the same fate as the father. When all was ready invitations were sent out to the neighbouring tribes to partake of the feast. The club with which the victim was to be dispatched was adorned with tassels and smeared with pounded egg-shells and then religiously secluded. The executioner painted himself grey with ashes and adorned his body with feathers, and after he had dispatched the prisoner (who was expected to show complete indifference to his fate), blood was drawn from the slayer's arm, and he was forced to retire to his hut for a time and lie in his hammock, amusing himself with a miniature bow and arrow to keep his eye in, this practice of seclusion and purification being intended doubtless to protest him from the angry ghosts of his victim. These rites and ceremonies, having been described by an eye-witness, are extremely valuable. Unfortunately the writer has added a wealth of detail which is merely sickening. He was determined that not a fraction of the horrors he had escaped should be lost on his readers.

Although Hans Staden was to some extent now an honoured guest among the Tupinambá, he was not to regain his liberty for a considerable period. A bitter disappointment awaited him, for a French ship which arrived to trade for pepper, monkeys and parrots refused to take him away for fear of offending the savages. The crew did not even give him a shirt to cover his nakedness. In his desperation Hans Staden made his one dash for liberty. He fled from his keepers and swam out to the boat, but the Frenchmen refused to take him in, and he was forced to swim back to the shore. Later he expressed the

8

hope that God would forgive these men, but it is

clear that he could not bring himself to do so, and on learning that the ship

must have foundered on the return voyage he remarks only that such cruelty and

want of pity could not go unpunished. When the next French ship arrived,

however, he found himself among friends. By means of a clever ruse he contrived

to be taken on board, and finally, amidst the lamentations of his captors, in

whose hands he had remained for nearly a year, he commenced his homeward

voyage. His perils were not yet over, for he was severely wounded in a skirmish

with a Portuguese vessel in the

The book appeared at

9

tedious introduction, but I do not believe it. Dryander certainly looked through the book, and probably corrected it here and there, but one has only to compare the introduction with the narrative to realize that if the learned Doctor's heavy hand had rested on Hans Staden's work its whole character would have been changed. Moreover, Hans Staden was in no sense a dullard. He learnt Portuguese and probably Spanish. He picked up the Tupi language and spoke it apparently with considerable fluency, and I see no reason why he could not have described his adventures in the very simple language which is one of the charms of his book. It would be difficult to see how a work of this description could be better arranged. In the first place we have a straightforward narrative of the author's personal adventures and misfortunes, written briefly and without any straining after effect. In the second part we have a treatise on the customs of the Tupinambá, their polity, trade, religion, manufactures and warlike undertakings, and of the flora and fauna of the country. This survey is the result of sustained and penetrating observation, and subsequent accounts have added little to the information given in it. Particularly interesting are the chapters devoted to the marriage ceremonies, government and laws, the personal adornment and religious observances of the people. Their gods were hollow gourds or pumpkins filled with stones, which when rattled were used for purposes of divination. In Chapter XXII, Part II there is a striking account of the blessing or bewitching of these rattles by the wise men who, in return for presents, imprisoned spirits in them with power to predict future events. The prisoner saw through the imposture at once, but to a simple unsuspecting audience it must have been a solemn and mysterious ceremony. Chapter XXIII, Part II contains an interesting description of the methods adopted

10

INTRODUCTION

to keep up the supply of cunning women, and in

Chapter XV, Part II there is an early reference to the tradition of the visit

of

Throughout his narrative Hans Staden shows himself as a curious mixture of simplicity and shrewdness. He was a very pious Lutheran and was ready to see the hand of God stretched out for his special safety in every disturbance of nature. The stories of the angry moon in Part I, Chapter XXX: of the miraculous cures (Chapter XXXIV): of the Cross in Chapter XLVI: of the thunderstorm in Chapter XLVII, are all regarded as the inevitable and immediate response to his prayers. He seemed to take the view that Hans Staden's perilous situation had been at last reported in the proper quarter and was now being satisfactorily dealt with. Up to a certain point the careful reader is conscious of an undercurrent of pained surprise, as if the unfortunate victim of fate was asking himself how in a world now purged of heresies such things could be allowed to happen to any pious Lutheran, and that a good deal was due to him if his contract with his Maker was to be honourably fulfilled. Once

11

he was conscious that God was on his side he was a little inclined to be presumptuous and self-centred. He was convinced, when asked to heal the sick, that his prayers would be answered, but he was seriously perturbed how to act, since he could not decide whether it would be more to his interest to let the sufferers die or live. We could wish that one or two episodes, particularly the episode in Chapter XXXIX, where a slave who had lied about him was killed and eaten, had been related in a different spirit, but it was part of the author's belief that all who wronged him should suffer both in this world and the next, and we must be careful not to judge him unfairly. It is certain that he had to face trials and dangers which would have tried the courage of many braver and more imaginative men. He was not a coward, and he really seems to have been more terrified of being eaten than of being killed. In any case we must remember that he willingly undertook the defence of the fort at Santo Amaro, which no Portuguese gunner would face, that he acquitted himself with distinction in action, and that when his captors had taken some Christian prisoners he remained by them to comfort and help them to meet their end, at a time when, apparently, he could have escaped quite easily.

The truth of Hans Staden's story does not seem ever to have been seriously questioned, although he obviously expected to be classed among the lying travellers. He is careful in his concluding address to the reader—a most convincing document—to mention the names of all Europeans with whom he came into contact, so that sceptics could check his statements. The learned Dryander, his sponsor, was a well-known man in his day, and he and the Landgrave of Hesse seem to have gone thoroughly into the matter, and to have cross-examined the traveller again and again without shaking him.

12

Moreover, the sources from which even a practised

writer could have compiled such a book were very few. Many of Hans Staden's statements are confirmed, in some cases strikingly

confirmed, by the French missionary, Jean de Léry,

who was actually in

It is interesting to know that H. J. Winckelmann, who published his work Der Americanischen Neuen Welt Beschreibung in 1664, while engaged among the archives at Cassel, discovered thirty-four of the original wood blocks used by Hans Staden and used them again, although he does not seem to have known of the existence of the various editions of Staden's book which were issued in 1557. Winckelmann also printed a portrait of the traveller, which presents him as a long-bearded, solemn-looking elderly man clasping a book in his left hand, but I do not reproduce it,

13

since a portrait produced for the first time a century after the sitter lived is open to a good deal of suspicion. It can be found at p. 3 of the facsimile reprint of Staden's book issued by the Frankfurter Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie and Urgeschichte, published at Frankfurt-a.-M. in 1927.

14

NOTE TO INTRODUCTION

THE full title of Hans Staden's book is as follows:

WARHAFTIG / HISTORIA UND BESCHREIBUNG EYNER LANDT- / SCHAFFT

DEDICIRT DEM DURCHLEUCHTIGEN HOCHGEBORNEN HERRN / H. PHILIPSEN LANDTGRAFF ZU HESSEN GRAFF ZU CATZEN- / ELNBOGEN DIETZ ZIEGENHAIN UND NIDDA SEINEM G. H.

MIT EYNER VORREDE D. JOH. DRYANDRI GENANT EYCHMAN / ORDINARII PROFESSORIS MEDICI ZU MARPURGK.

INHALT

[

There were three reprints in 1557. For these and the subsequent history of

the book see Viktor Hantzsch, Deutsche Reisende des 16.

Jahrhunderts (in Leipziger

Studien aus dem Gebiet der

Geschichte, Bd. I),

15

Richard N. Wegner), Frankfurt-a.-M., 1927, pp. 19-24. This facsimile was

published by the Frankfurter Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie, und Urgeschichte. A

short bibliography is appended to the Hakluyt Society's translation issued in

1874. There is an excellent reprint of the

Hans Staden has received a good deal of study in

16

NOTE TO INTRODUCTION

Richard N. Wegner's Begleitschrift to

the facsimile reprint issued at Frankfurt-a.-M. in

1927, referred to above, brings together all that is known about Hans Staden and his book, and contains an interesting survey of

the earlier and later literature of discovery. Southey in his History of

Brazil,

It seems to have escaped the notice of Hans Staden's editors that his book was well known to Purchas. In the volume (reprint, vol. xvii, p. 56) containing the extracts translated from another German traveller in Brazil of about the same period, Ulrich Schmidel, whom Purchas elects for the most part to call Hulderike Schnirdel, the editor has added the following note: "I had thought here to have added the Voyages of Johannes Stadius (another German which served the Portugals in Brasill about Schmidel's later time) published in Theodore de Bry; and had the same by me translated. But contayning little light for the Countrie and People, and relating in manner onely his owne Tragedies, in his taking by the Savages, and often perils of being eaten by them, as some of his friends were before his face, with other like Savage arguments wherewith wee have glutted you alreadie: I being alreadie too voluminous, have omitted the same and hasten to other Relations."

While taking exception to Purchas's views concerning the general interest and value of Hans Staden's travels, we must indeed regret the loss of a 17th-century version of the book, rendered, we may be sure, with all the raciness and style which characterizes every page of "Purchas, His Pilgrimes." To be able to describe the roasting and eating of human beings as a "Savage argument" is a luxury denied to the translator of today.

1 7 C

THE TRUE HISTORY

DEDICATED TO THE SERENE

18

To the Serene and Highborn Prince and Lord, Philip, Landgrave of Hesse, Count of Catzenelnbogen, Dietz, Ziegenhain and Nidda etc., my gracious Prince and Master.1

Mercy and peace in Christ Jesus our Saviour. Most gracious Prince and Lord. The holy King and Prophet David speaks in the hundred and seventh Psalm:

They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters:

These see the works of the Lord and his wonders in the deep.

For he commandeth and raiseth the stormy wind, which lifteth up the waves thereof.

They mount up to the heaven, they go down again to the depths: their soul is melted because of trouble.

They reel to and fro, and stagger like a drunken man, and are at their wit's end.

Then they cry unto the Lord in their trouble, and he bringeth them out of their distresses.

He maketh the storm a calm, so that the waves thereof are fill.

Then are they glad because they be quiet; so he bringeth them unto their desired haven.

Oh that men would praise the Lord for his goodness, and for his wonderful works to the children of men!

Let them exalt him also in the congregation of the people, and praise him in the assembly of the elders.

So do I thank the Almighty Creator of the Heavens, the Earth and the Seas, his Son Jesus Christ and the Holy Ghost, who showed mercy and pity to me among

19

the savage peoples of Brazil called Tupin Imba, eaters of men's flesh, who took me captive and whose prisoner I was for nine months amidst many dangers, and who delivered me in safety through their Holy Trinity by means wholly unlooked for and most wonderful. I thank God also that now, after so much misery and danger, I am once again after many years in these dominions, my beloved home, where I hasten dutifully to give an account of my travels and voyages, which I have described as briefly as may be. I trust that your Highness may be pleased to have read aloud at your leisure the story of my adventures by land and sea, if only on account of God's wonderful mercies vouchsafed to me in my distress. And lest your Highness should think that I have reported untrue things, I venture to offer your Highness at the same time a sponsor for my veracity. To God alone and all in all be the glory. I commend myself to your Highness in all humility.

Dated at Wolfhagen, the twentieth day of June, Anno Domini, Fifteen Hundred and Fifty-Six.

Your Highness's subject Hans Staden of Homberg in Hesse, now a burgher of Wolfhagen.

20

DR. DRYANDER'S INTRODUCTION

To the noble Lord, the Lord Philip Count of

Hans Staden, who now offers this history in print,

has asked me to read his work, to revise it and where necessary to correct it.

I have complied with his request for various reasons. Firstly, I have known his

father for upwards of fifty years, for he and I were born and taught in the

same town, namely Wetter. Both in his home and in Homberg

in

Further, I approached the labour of revising this book with all the more pleasure and satisfaction, since I delight in matters appertaining to mathematics, such as cosmography, that is the measuring and description of countries, towns and highways, of which much will be found in these pages. I employ myself the more willingly in such matters when I know that the writer relates and discloses, in truth and honesty, only such things as have befallen him. I believe that Hans Staden has faithfully reported his history and adventures from his own experiences and not from the accounts of others, that he has no intent to deceive, and that he desires no reward or worldly renown, but only the glory of God, in humble praise and thankfulness for his escapes. This is indeed the chief

21

purpose of the work, that men may see how mercifully and against all hope the Lord God delivered Hans Staden, who called upon him, out of so many and great dangers; how he rescued him from the savage people in whose power he lay for nine months in daily and hourly expectation that he would be killed and eaten, and how he restored him in safety to his father-land in Hesse.

For these unspeakable mercies he desires, as far as in him lies, to give thanks to God and, praising him, to make his blessings known to all men, and in the laborious ordering of this work to relate in detail his journeys and the chances which befell him during his absence of nine years from his country. All this he relates simply and without ornament or great words or arguments, a fact which impresses me with the truth of what he describes. I do not see what advantage he could obtain by lying, even if he preferred falsehood to the truth.

In addition, he is now settled with his parents in this country. He does not wander from place to place, gipsy-like, a practice common among vagabonds and liars in general, and he must therefore expect to encounter other travellers on their return from the same islands who could convict him of falsehood if he were lying. This fact is also a convincing argument to me that his history is truthfully related, that he is careful to indicate the time, country and place of his meeting with Heliodorus, son of the learned and widely-famed Eoban of Hesse3 who has now been long absent on a voyage of discovery in foreign parts and was believed by all of us to be dead. This Heliodorus was with Hans Staden in the country of the savages and observed his misfortune when he was taken and carried away. This same Heliodorus, I say, may return sooner or later to his home (as is indeed to be hoped), and if Hans Staden's history is a

22

DRYANDER'S INTRODUCTION

false and lying history, he will be able to put him to shame and denounce him as a worthless person.

I will now leave the weighty arguments and conjectures which support Hans Staden's integrity and consider briefly why it is that histories of this kind receive generally so little credit and applause.

In the first place, land travellers with their boundless falsehoods and reports of vain and imagined things have so wrought that honest and worthy people returning from foreign countries are now hardly believed. For it is commonly said: he who desires to lie, let him lie concerning far off things and places, since few travel into distant parts, and a man will sooner credit what he hears than undertake the labour of finding out the truth for himself.

But let it not be assumed that truth is to be silenced by falsehood. It is to be noted that many matters appear to the common people to be incredible, yet when they are disclosed to men of understanding and thoroughly tested they are found to be known and proved, and to be in themselves worthy of credence.

This fact is clear if we take two examples from astronomy. We who live in

When it is reported, therefore, that somewhere in the world the sun does not set for half a year, that the longest: day and the longest night endure each for six months, that is half a year; further, that in certain places the quatuor tempora or four seasons are duplicated, and two winters and two summers succeed each other in the course of the same year; likewise, that the sun and the stars, how small soever they appear to us, yet is the smallest star in the heavens greater

23

than the whole earth, nor can their number be measured:—when the common people hear these things they condemn them as impossible and not to be believed. Yet these are matters within the knowledge of astronomers, and no one skilled in science can doubt that they are true.

It does not follow, then, that these things are false because the common people think them so. Nevertheless, the science of astronomy would stand low indeed if persons who profess that science could not foretell the times of the eclipses and when and for how long the sun and moon shall be darkened. These happenings have been foretold hundreds of years in advance, and men have found them to be correct. Yet some will say: "Who has traversed the heavens and measured them and beheld these things?" To this I make answer that the experience of every day confirms the evidence of the learned, as clearly as I can demonstrate that two and three make five. Facts and scientific demonstrations have established that it is possible to measure and calculate the situation of the moon, the distance of the planets, and the height of the starry heavens, the size and circumference of the sun, moon and other heavenly bodies, and with the aid of astronomy and geometry to establish the distance, circumference, breadth and length of the earth itself. Yet these matters are hidden from the common mind and are generally believed to be impossible. The ignorance of the ordinary man may be attributed to the fact that he has no knowledge of philosophy, but that learned and scientific persons should doubt of matters so definitely established is both shameful and dangerous, for the common man looks up to the learned and observes their dissensions, remarking: "If these things were true, so and so would not have disputed them." Ergo, etc.

24

DRYANDER'S INTRODUCTION

holy and learned men as well in theology as in the

arts) doubted the existence of the antipodes. They denied that men could

inhabit the opposite sides of the earth and exist beneath us, walking with

their feet uppermost and their heads hanging down towards the skies without

falling off. This may indeed sound strange, but learned men questioned it, and

it has been found to be true in the face of the denial by the holy and learned

authors I have named. For it follows that those who live ex diametro per centrum terræ must be antipodal, for omne

versus cœlum vergens, ubicunque locorum sursum est. Nor is it

necessary for us to travel downwards unto the

Certain pious theologians maintain from this that the words of the mother of

the sons of Zebedee have been fulfilled, when she desired of the Lord Jesus

that her two sons might sit the one on his right hand and the other on his

left. This, they say, has been fulfilled in that St. James lies buried at Compostella, at the end of the earth, which is called

Finisterre, where he is held in honour, and the other

apostle rests in

25

the lower hemisphere beneath us is buried deep down

in the sea and is without life. But all this is contrary to the science of

cosmography, for the many voyages of the Spaniards and Portuguese have

established the exact opposite, that the globe is everywhere inhabited, yea,

even the

These and similar arguments may be read in the book written by the worthy and learned Magister Caspar Goldtworm,5 your Highness's diligent superintendent and chaplain at Weilburg, which book is divided into six parts and treats of miracles, wonders, and paradoxes of former and present times, and which will shortly be printed. To this work, and to many others dealing with such matters, such as Libri Galeotti, de rebus vulgo incredibilibus,6 I refer the friendly reader who desires further instruction and understanding.

Let it be made clear that matters which are strange and ridiculous to the common mind must not straightway be condemned as lies. The island people described in this book go naked; they have no domestic beasts for food, none of those things, in fact, which are common to us for the support of the body, such as clothes, beds, horses, pigs or cows, not even wine and beer, but they contrive to maintain themselves in their own way.

Now in order that this introduction may have an end I will briefly explain why it is that Hans Staden

26

DRYANDER'S INTRODUCTION

has been moved to complete and print the story of his two voyages. Some may take it amiss, as if the writer desired his own glory or to make a great name for himself. I know that this is not so and that his disposition, as appears from several indications in the history itself, is very different.

Such was his misery and so great his adversity, and so constantly was his life in peril and the victim himself without hope, that he had abandoned all expectation of gaining his liberty, or of seeing his home again. Yet God, in whom he trusted and upon whom he called, did not leave him helpless in the hands of his enemies, but was moved also by his prayers to manifest himself to the heathen, that they might see and know that the only true God, mighty and all-powerful, was at hand. To the prayers of the faithful there is neither limit nor restraint, and it pleased God through Hans Staden to show his mighty works among the heathen. This, in truth, cannot be denied.

It is known also to all men that sorrow, care, misfortune and sickness turn

men's thoughts towards God: then do they cry to him in their despair. Some

hitherto among the papists invoke this saint or that holy one, vowing

pilgrimages or offerings that they may be saved from their perils. These vows

are commonly well kept, except among such as seek to deceive the saints with

empty promises. Erasmus Roterodamus in his colloquy

on Shipwrecks writes of one who cried in the ship to St. Christopher, whose

image, standing some ten ells high like a great Polyphemus,

may be seen in

27

him: "If he delivers me from this, he will not get so much as a farthing candle from me."

Another dory concerns a knight, who was also in danger of shipwreck, and it is as follows. This knight, when he saw that the ship was about to founder, called to St. Nicholas and vowed that if he would save him in his need he would offer him his sword or his page. His squire thereupon reproached him and asked him how he would ride abroad if he did this. "Hold thy peace," said the knight under his breath, led the saint might hear, "let him only save me, and I shall not give him even the tail of my horse." So did these two make their plans to deceive their patron saints, intending to forget speedily the benefits vouchsafed to them.

Led Hans Staden should be regarded as a man ready to forget his mercies now that God has succoured him, he desires in printing his history to give honour and praise to God alone, and in all Christian humility to make known to men the mercies vouchsafed to him. If this were not his intention (which is indeed both honourable and fitting), he would surely have spared himself the labour and time, to say nothing of the charges of printing this work and cutting the blocks, which alone have been considerable.

Since this history has been inscribed by the author to the Serene and Noble Prince and Lord, the Lord Philip, Landgrave of Hesse, Count of Catzenelnbogen, Dietz, Ziegenhain and Nidda, his Prince and gracious Master, in whose name it has been published, and since the author has long before been interrogated in my presence and in the presence of many others by his Highness, our gracious Lord, and examined closely in all matters touching his voyages and captivity (all which I have many times dutifully reported to your Highness and to other Lords), and knowing your Highness to be a great lover of such things, and of all

28

DRYANDER'S INTRODUCTION

that appertains to astronomy and cosmography, I have therefore addressed my preface to your Highness, begging that it may suffice until such time as I am able to publish in your Highness's name something more weighty.

I subscribe myself in all humility.

Dated at

29

THE CONTENTS OF THIS BOOK

1. Of the two voyages which Hans Staden undertook in

eight and a half years.7 The first journey

was from

2. In what manner he was carried to the country of the savage people Toppinikin (who are subject to the King of Portugal), where he was employed as a gunner against the enemy; and how at last he was captured by the enemy and carried away and remained for nine and a half months a prisoner with them in danger of being killed and devoured.

3. How God in merciful and wonderful manner delivered him from his enemies and restored him to his fatherland.

All which is now related in print to the honour and glory of God and in thankfulness for his wondrous mercies.

30

31

NOTES

1 Philip I, the Magnanimous, of

2 Dryander, or Eichmann, one of the most famous of German anatomists, was born at Wetterau,

studied medicine at

3 This was Helius Eobanus Hessus, humanist, born

4 A Franciscan who died in

5 Goldtworm was a Lutheran preacher. He is known as the compiler

of a church calendar, but his promised book on miracles and wonders does not

seem to have been printed.

6 Galeotti-Mario,

astronomer, Professor at

7 The eight and a half years must refer to

the period between Staden's first leaving home and

his final return. The first voyage lasted sixteen months, from

This electronic edition scanned and edited by http://www.jrbooksonline.com July 2006