Excerpt from Vincent Reynouard Gestapo Articles

Introduction by C.W. Porter

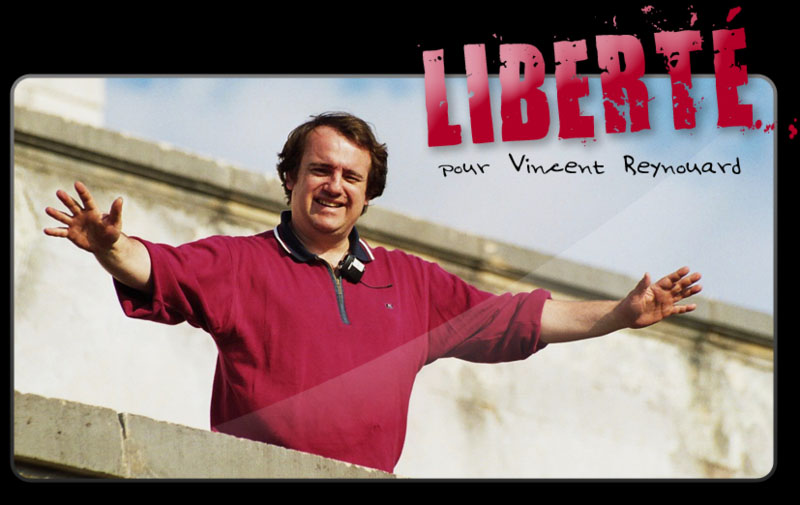

Vincent Reynouard, currently vacationing at Valenciennes [jail], had a brain-storm, one of the smartest revisionist ideas I ever heard of:

he took the trouble to compare the accusations made against the Gestapo at Nuremberg, by the French, with the post-war French trials of the same personnel, involving the same cases, the same victims, the same witnesses. What he found was that the evidence and accusations were not the same: the accusations made at Nuremberg in these same cases were practically forgotten.

His articles constitute some of the best proof I ever saw that the Nuremberg "evidence" was just lies, all lies.

This is just an example.

For alternative introductory remarks, click here.

C.P.

October 7, 2010

WHY THE REVISIONISTS ARE FEARED

"You're a man who makes people afraid. That's dangerous."

"It's what they know about themselves inside that makes them afraid."

-Clint Eastwood, High Plains Drifter

Gestapo behaviour towards women and young girls

False nature of the official claims

Despite the evidence, the French prosecutor at Nuremberg dared to declare:

“Those who carried out these measures had every latitude for unleashing their instinct of cruelty and of sadism towards their victims” [IMT V, 401]. Supposing this to be true, these agents are said to have exploited women who fell into their hands. This is untrue.

Of course, in his report, cited above, H. Paucot wrote that, during the interrogations, "The women and young girls were… almost always completely undressed, out of pure sadism” [“Les femmes et les jeunes filles étaient traitées de la même façon [que les hommes] et sadiquement étaient presque toujours complètement dévetues” (doc. F-571, IMT XXXVII, 263) [XXX, same document].

But this is untrue: in the thousands of pages which I had taken the trouble to read, there is no question of undressing [except for one case involving a common-place theft perpetrated by two members of the “Bonny-Lafon gang”. The thieves totured and undressed an old woman and her nurse to force them to reveal the hiding place of their savings. The two victims were then murdered. In this lamentable affair, the individuals were acting, not as agents in the German service, but as common criminals in search of material gain, etc.] Otherwise, there is no question of rape or even improper gestures or touching.

Mlle Phegnon suffered no humilation

At the “Neuilly Gestapo Trial”, Colette Phegnon, the daughter of the local Resistance leader, described her interrogation; while she claimed to have been beaten or struck (see above), she mentions no undressing, no torture. In this regard, she contented herself with saying: “ [R. Martin] threatened me with the bathtub treatment. But they didn’t go through with it.” (PGN, 5, 96).

No “inappropriate gestures” with regards to Mlle Lelong

Even more clearly, the following is the deposition of Mlle Lelong, who recalled her treatment (fully dressed), but tied to a chair and beaten by Gestapo agent M. Beller:

"THE PRESIDENT. — No inappropriate touching?

Mlle LELONG. — No.

THE PRESIDENT. — I like that better" [PAFG, hearing of 1 March 1947, deposition of Jacqueline Lelong, p. 24].

Mme Memain spoke of "rather correct” police agents …

Two years before, another Resistance member, Mme Memain, was asked a similar question and gave a similar response:

“THE PRESIDENT. — […] Did those in the lodge act appropriately towards yourself, Mlle Genet and others?

Mme MEMAIN. — They were rather correct” [PGG, dossier 10, p. 117.]

Mme Thierry speaks of “correct” agents as well

At the Bonny-Lafon trial, a woman whom he had already questioned, F. Thierry, was also questioned as to the manner in which she had been interrogated:

“Me DELAUNEY. – […] you were released, after an interrogation, which was courteous, I believe?

THE WITNESS. – It was correct“ [PLB, 6, p. 167, deposition of Françoise Thierry].

Treatment of pregnant women

The prosecution spoke of pregnant women beaten until they suffered miscarriages…

At Nuremberg, the French prosecution produced a terrible written declaration by Major Pierre Loranger. After investigating the acts of the German police services in France under the occupation, he wrote:

“To the physical torments, the sadism of their torturers added the particularly painful moral torment for a woman or young girl of being undressed and stripped naked by her torturers. The condition of pregnancy did not protect them from blows and when the brutalities entailed the expulsion of the product of conception, they were left without care, exposed to all the accidents and complications of this criminal abortion.”

[“Aux supplices physiques, le sadisme de leurs tortionnaires ajoutait le supplice moral particulièrement pénible pour une femme ou une jeune fille d’être dévetue et mise a nu par ses bourreaux: L’état de grossesse ne les présérvait pas des coups et lorsque les brutalités entrainaient l’expulsion du produit de conception, elles étaient laissées sans soins, exposées à tous les accidents et toutes les complications de ce criminel avortement” [IMT, XXXVII, 297]; [see also IMT XXX, same document]:

These accusations are not confirmed by any testimony whatever

The following are three written testimonies from women and one from a man, but concerning his wife. One expects to find four terrible tales of forced nudity, inhuman torments inflicted upon pregnant women and resulting miscarriages. But we find nothing of the kind: no nudity, no humiliation, no miscarriages due to beatings, etc:

- Lucienne Krasnoploski was not mistreated at all; employed for two months as a cleaning lady at the Kommandantur of Valenciennes, she would have seen people beaten and tortured (Ibid., pp. 299-300).

- Madame Carton, a barmaid who failed to serve the Germans fast enough, received a hard slap which perforated her ear drum (pp. 297-8).

- Madame Hazard, whose husband was "the head of a Resistance group” is said to have been beaten with a whip “with extreme violence” [“avec la dernière violence”], but without causing any fractures, which “stupefied” the physician (p. 298).

It should be noted that these women were not pregnant. The only one who was pregnant, was named Gilberte Sindemans. She was a young Resistance member, aged 22. On 24 February 1944, she was arrested in a hotel in Paris. A search permitted the discovery of the affair of the stamps from the Kommandatur, “laissez-passer” cards [a sort of internal passport], German worker identification cards (stolen the evening before) as well as box of cartridges and three revolvers (IMT, XXXVII, 298). She was obviously a major activist! The following is what she writes:

“They immediately put me in handcuffs and took me away for interrogation. As I did not answer, they slapped me right across the face with such force that I fell off my chair. They whipped with a rubber whip, right across the face […].

I had to tell them I was three months pregnant.

After my first interrogation, I was taken to the prison of Fresnes and I was thrown into a solitary confinement cell without a mattress, without blankets, with my hands handcuffed behind my back at all times, plus I had chains on my ankles. For 4 days, without anything to eat or drink. On the 4th day, they came for me, to interrogate me. I underwent 24 interrogations and I came back with my face more and more swollen up every time. Since I wouldn’t say anything, they threatened to deport me for execution by shooting. Since I still wouldn’t talk, they put me in a cell for six months, in secrecy.

There came the day of the evacuation of the prison. As I was expecting my baby, I expected to be released, but I received a visit from the commissioner and the chaplain. They told me my last [hour] had come and I had to talk […].

I was taken to the Fort de Romainville and from there to the hospital, where I had my little girl, on 25 August” [IMT, XXXVII, 299].

Of course, her story is quite regrettable. But if one does not wish to be beaten and endanger the life of one’s baby, one should not participate in an illegal war; one should not steal official papers and stamps from the enemy, and one should not deal in weapons under a military occupation. In addition, I must stress that G. Sindemans was never undressed, and above all, she never received any blows which could have endangered the life of her baby. On the contrary: in the end, she was allowed to give birth to her little girl, alive and apparently healthy. Proof that, although she was detained in secrecy, she received no other mistreatment.

Consequently, these four testimonies in no way prove the allegations made by Major Loranger. Now, it is obvious that if the French prosecuting authorities in these post-war trials had really been in a position to produce any such testimony, even in one single case, they certainly would have done so.

Today, thus, it is permissible to conclude that Major Loranger’s allegations have no reliable basis in fact.

The dishonesty of the Nuremberg prosecution

It is also interesting to note that, at Nuremberg, the assistant prosecutor C. Dubost read the declaration of Major Loranger’s written statement, and went on to quote the deposition of this same G. Sidemans (since the other three prosecutors offered no evidence). Dubost took great pains, however, to delete the end of that same deposition, reading only the first three lines [IMT VI-171], and stopping just after the words “I must tell you that I was three months pregnant at that time”.

In other words, Dubost concealed the fact that G. Sindemans was permitted to give birth to a little girl in the end (IMT VI, 179-180) -- thus giving the Tribunal – and the world – the impression that this courageous Resistance member had — like so many others — lost her child as a result of German mistreatment… It is hard to be more dishonest than that…

Case of women Resistance members: proof that the Gestapo acted with great restraint, even in serious cases

Having stated the above, let us proceed. Under the Occupation, in visiting people’s homes to arrest suspected members of the Resistance, the Gestapo auxiliaries very often found themselves face to face with the wives of these same, wanted individuals. How did they treat these women? Did they strip them naked? Torture them? Beat them and strike them until they suffered miscarriages?

Not at all.

Case of Mme Lecour

Let us first take the case of Mme Lecour, from Cours-Cheverny. Her husband was a wanted Resistance member. On 30 July 1944, French auxiliaries came to her house. But the man was not there; he had taken refuge elsewhere. At the house, the group found only the wife, then seven months pregnant, with her baby.

What did they do? At their trial, the statement of facts says:

“Mme Lecour, seven months pregnant and alone with a one-year old baby, was at home when Combier and his team appeared. These individuals conducted a search of the house according to the regulations and attempted to obtain information as to Lecour’s whereabouts by threatening her with their weapons. Combier was mean enough to give Mme Lecour a few slaps, despite her condition” [PAFG, statement of facts, p. 20].

At the hearing, the husband appeared as a witness:

“THE PRESIDENT. — What did they do to your wife?

M. LECOUR. — They hit her.

THE PRESIDENT. — They searched the house?

M. LECOUR. — Yes, they did […].

THE PRESIDENT. — Did they hit your wife despite her condition?

M. LECOUR. — Yes.

THE PRESIDENT. — How did they hit her?

M. LECOUR. — They hit her and pulled her hair” [PAFG, hearing of 1 March 1947, deposition of M. Lecour, p. 216].

The wife then testified as follows:

“THE PRESIDENT. — [...] Did one of them enter the house and slap you?

Mme LECOUR. — They hit me and pulled my hair” [Ibid., p. 219].

One must, of course, condemn the violence inflicted on this woman. But, if we were to believe Major Loranger and all the other propagandists, these same individuals – Gestapo auxiliaries -- should have had recourse to much more terrible means of making her talk: they could have taken her baby and said, “Talk, or we’ll cut one ear off, then the other one, etc” ; they could have abducted the child and told the mother "We’ll give her back when you talk”; they could have stripped her naked, placed the woman on her back, and told her: “Talk, or we’ll stomp on your stomach”.

They did nothing of the kind. They abstained from acting in this manner, and they left without even learning the whereabouts of the wanted man, the very same Resistance member they came to arrest…

Search at M. Buffet

From Cours-Cheverny, now let’s look at Lyon. The members of the “Georgia Gestapo” at Lyon were searching for a very important wanted Resistance member, M. Buffet. Having visited his home and having failed to find him, they conducted a search according to the regulations:

“THE WITNESS [Mme Buffet]. — [...] You tipped everything over, my mattresses, everything...

OBERSCHMUCKLER. — You are right.

REBOUL. — [...] The search was completed?

THE WITNESS. — Yes.

REBOUL. — The mattresses were tipped over?

THE WITNESS. — The drawers, everything, on the floor!” [PGG, dossier 8, p. 94]

The agents found nothing capable of revealing the whereabouts of M. Buffet. In the house, however, were his wife and daughter. Not surprisingly, they attempted to extort information from the mother. The statement of facts declares that Oberschmuckler “interrogated her very severely and made numerous threats” (PGG, statment of facts, p. 83).

But did he beat her, torture her? No. The follow-up permits us to answer that question: H. Oberschmuckler, we are informed “backed Mme Buffet up against the wall at pistol point” (Id.). That’s all…

In 1945, moreover, when called as a witness, Mme Buffet never even mentioned any of this inhumane treatment to which she had allegedly been subjected! This is what she declared:

“On 5 February 1944, towards 11 o’clock in the morning, three individuals came to my apartment, produced a pistol, and conducted a search of the premises. They found nothing, of course, and they questioned me about what my husband did, what was going on in his garage. I answered that I didn’t know anything, that I wasn’t aware of any of these things. They then questioned me about a certain Georges, who is now commander Jouneau. I said I didn’t know who this person was, I didn’t know him. Seeing that they weren’t getting anywhere, they remained in the apartment for an hour. They questioned me about my husband’s family, asking me where they lived, and they left. The next day, Sunday morning, three other individuals appeared. They weren’t the same men. They questioned me again. They searched the place again, and then they left” [PGG, dossier 8, p. 86, deposition de Mme Mathilde Vernay, wife of M. Buffet].

Shortly afterwards, the President of the Tribunal interrogated her about any threats made:

“THE PRESIDENT. — You indicate that he [the chief] did not threaten you. Didn’t you indicate that he was the one who threatened you?

THE WITNESS. — He held his pistol against me.

THE PRESIDENT. — He held the pistol?

THE WITNESS. — Yes.

THE PRESIDENT. — It was Oberschmuckler who held the pistol against you and forced you against the wall?

THE WITNESS. — Yes, that’s correct. I didn’t move, by the way. I remained motionless during the entire search and interrogation” [Ibid., p. 88-9].

She was then questioned by Government Commissioner Reboul:

“Reboul. — Weren’t you threatened during the first search?

THE WITNESS. — No. They simply told me to keep calm […] I told them I didn’t know what my husband did. They told me that I could keep silent, but that if they found my husband, his case would be closed” [Ibid., p. 90].

Now, Mme Buffet was perfectly well aware of both her husband’s activities and his whereabouts. During the trial, she mocked Oberschmuckler proudly and openly, right there in the courtroom, saying: “I really took you for a ride!” (Ibid., p. 95).

I think one can safely suppose, however, that if these same of Gestapo agents had undressed her, beaten her severely, burnt the "sensitive” parts of her body, forced splintered matches under her fingernails and set fire to them, or cut her daughter’s ears off, the same woman would have talked. But the point is: they didn’t do it.

It should also be noted that after the search, the members of the "Georgia Gestapo” were actively looking for M. Buffet. They showed photos of him to various people in the neighbourhood asked if they knew him:

“They went walking around the district with enlarged photographs and asked everybody is they knew me” (PGG, dossier 8, p. 66);

“Reboul. — I say that the witness is providing us with a new fact, it is that after this matter, they looked for him everywhere, walking about the area with photographs that they had taken the trouble to enlarge.” (Id.).

In reality, the photos had been enlarged by Mme Buffet eight years before (Ibid., p. 135)].

Now, this Resistance member had a mother and parents-in-law. The Gestapo could therefore have arrested them all and warned M. Buffet that his family would only be released if he turned himself in; they could even have demanded his surrender in the form of an ultimatum. But they didn’t do so; they merely arrested his nephew by mistake, Georges Buffet, because they believed him to be the “Georges” in the Resistance whom they were looking for.

Not only didn’t they torture people, they offered them cash rewards

OK, now let’s talk about “Georges”. This person was really M. Jouneau, “whom Oberschmuckler was actively looking for” (Ibid., p. 84). In accordance with normal procedure, the auxiliaries arrived to search his domicile. Not surprisingly, “Georges” was not there; the search team found only his wife and children. According to the statement of facts read out during the trial on July 1945, H. Oberschmuckler “behaved abominably” (PGG, dossier 1, p. 84).

But what did he do? Did he torture the wife, or torture their children under the mother’s eyes, to make her talk? No. We read:

“He attempted to bribe Mme Jouneau by offering her money and undressed one of the children to be sure which sex it was. He then left after two hours of interrogations and stealing furs and personal effects” [Id].

At the hearing, Oberschmuckler denied this and accused another person:

[Mme Jounaud] is getting me mixed up with Krammer. Krammer, who was present, said to her: if you give me M. Jouneau’s address, I’ll give you a hundred thousand francs; and he showed her a packet of money [...] As regards the act of undressing a little girl — a little girl six months old — I would like to point out that the child was lying in a little bed, on top of a leather jacket [...] A German lifted the child up, took the leather jacket and stole it. The woman then thought that we had looked at the child — a little girl six months old — but she will [also] confirm that if the German really lifted the child up, it was to steal something” [PGG, dossier 3, p. 98].

Nevertheless, when called as a witness, M. Jouneau accused H. Oberschmuckler, and said:

“ […] the children interested him in particular, especially my older daughter, who was two years old at the time, and looked a little bit like a boy. Boys interested him, this character, and he stated that he had what he needed to keep himself busy [il a precisé qu’il avait ce qu’il fallait pour s’en occuper]. I am very happy that he didn’t have to do it [qu’il n’ait pas eu à le faire].

“ [...] This happened at 8 o’clock in the morning, and lasted until 11, when the search was over. Oberschmuckler looked through everything there was, that is, the money, first. He put 100,000 francs on the table, this rascal, as a reward for turning me in. She’s worth more than that, Monsieur Oberschmuckler, you didn’t know the brave spirit that motivates the French Resistance members. You could have offered ten times as much. You would never have mixed them up in your dirty work!” [Applause in the courtroom].

“On the other hand, he had given the order not to move [or remove: enlever] the children. He waited until the search was more nearly complete.

“No need to tell you that my wife is used to this sort of repression: this was the third time. The next day, she moved, without wasting time [PGG, dossier 8, p. 139].

What’s the main point of all this? That to make the woman talk, members of the “Georgia Gestapo” used no violence at all: they didn’t torture the mother; they didn’t strip her naked and beat her; they didn’t torture or molest the children in front of her eyes, to force her to talk. On the contrary. No -- they tried to get her to talk by offering her money…

No brutality against Mme Cléret

Let’s get back to Paris and the case of the PTT. The German police were looking for M. Cléret, one of the leading Resistance members, as well as for his men. Members of the “Georgia Gestapo” went to his home and found only his wife. She had gone to take refuge in Seine-et-Oise pour “to avoid arrest, which she felt to be imminent” [PGG, statement of facts, p. 66].

They interrogated the wife, who refused to talk. What happened then? Was she beaten, tortured, electrocuted, burnt with acid? All these accusations, and more, were made at Nuremberg:

“Special mention must be reserved for the more refined tortures […] incisions between the toes upon which they poured a corrosive liquid, cleverly-dosed electrical shocks which caused all the muscles to convulse…

-- [“Il faut reserver une mention speciale à des supplices plus raffinés: […] incisions entre les orteils sur lesquels on versait un liquide corrosif, les courants éléctriques bien dosés qui convulsaient tous les muscles” (see the above-mentioned report by H. Paucot, IMT XXXVII, p. 264)] --

“or with a lighted cigar applied to her breasts [“I personally saw a young woman who bore on her breasts the scars from burns inflicted with a lighted cigar”]

-- [“J’ai personnellement vu une jeune femme qui portait sur les seins les cicatrices de brûlures faites avec un cigare allumé” (Ibid., p. 265)] --

“given the bathtub treatment…

“immersion in a bath of icy water was a common practice…

-- “l’immersion dans un bain d’eau glacée leur état familière” (Ibid., p. 263).

What did they do, in fact? Let’s let her talk, the victim.

On 23 July 1945, Mme Komarov, whose married name was Cléret, testified as follows before the High Court:

“Mme KOMAROV. — […] They showed me photographs of people who were Resistance members from the PTT [Post, Telegraph and Telephone] and who had been arrested and they asked me to identify them. Since I refused to do so, and said that I didn’t wish to talk, they took me to Rue des Saussaies to make me talk, then Fresnes.

At Rue des Saussaies, they showed me photographs. They wanted me to admit that I knew these people, that my husband was a dreadful person, a murderer, a whole load of stuff.

An hour and a half later, I was taken to Fresnes. During this time, these men were busy pillaging everything in our home […].

THE PRESIDENT. — You were not brutalised while these men were in your home?

Mme KOMAROV. — No, I was not brutalised. I was insulted” [PGG, dossier 11, pp. 3-4].

The truth of the matter could not possibly be clearer: although this was a rather serious case, Mme Cléret, who refused to talk, was not mistreated, merely insulted.

I should add that, informed of his wife’s arrest, M. Cléret did "everything possible to get her released. Through friends, he succeeded in contacting one of Odicharia’s lieutenants [...] who asked M. Cléret for 150,000 Frs for obtaining her release. Cléret handed it over and Mme Cléret was released on 7 August 1944” (PGG, dossier 1 p. 67). At the hearing, M. Cléret confirmed: “I believe it was rather because of the 150,000 francs that she was able to get out of prison” [PGG, dossier 11, p. 9].

The simple ruse against Mme Meley

Let’s us remain with Paris. In connection with the dismantling of a Resistance network, the German police were looking for a certain M. Meley, head of the organisation. But he had fled, leaving his wife alone at home. Auxiliaries of the German police attempted to obtain information from the wife.

Again, did they use torture, the whip, acid, electricity? Once again, no. Instead, they merely tried a trick:

1°) On 20 June1944, G. Collignon passed himself off as a Resistance member wishing to see M. Meley. Mme Meley contented herself with saying “My husband is not there” . G. Collignon withdrew (PGG, dossier 1, p. 67).

2°) Eight days later, Gestapo agents came to the apartment at midnight " turned the place upside down, searched everywhere” (Ibid., p. 68). They remained for some time, organising surveillance in relays so as to arrest M. Meley when he came back. But he didn’t show up, so they gave up. Mme Meley was not even arrested (Id.).

Same strategme is used against Mme Viard

In the same case, the Gestapo attempted to arrest Georges Viard but he had fled, as well, leaving only his wife. On 28 June1944, two agents appeared at the home and passed themselves off as Resistance members wishing to know Viard’s whereabouts. Mme Viard maintained a cautious silence.

The intruders did not even attempt to conduct a search.“Then they gave me a telephone number [...] and asked me to notify them if my husband came back. Mme Viard promised, did nothing, and never saw these two individuals again” .

During the “Georgia Gestapo” trial, one of the accused, Solina, admitted that he had conducted a search at Mme Viard’s, but confirmed this version of the facts:

"Mme Viard simply said that her husband was away. We said: ‘Please tell your husband to telephone M. Totor’. We didn’t even search the house, while we could have gone in all the rooms and checked anything we wanted" (PGG, dossier 3, pp. 59-60).

The surprising admission of a woman who was not mistreated, either

Let us finish with the case of M. and Mme Marceron, a married couple in the Resistance, who were concealing six cases of explosives in their home. They were betrayed by a woman who talked after being arrested. When agents in the German service arrived, they knew what they ought to find. Not surprisingly, the couple denied everything:

“My husband replied, smiling, that they obviously weren’t the kind of people who kept explosives around the house […]. I answered in the same vein, that I didn’t understand what they were talking about” (PBL, 7, p. 52, deposition of Mme Marceron)].

The woman had her small child with her, aged 2 and a half. The agents, who had no time to waste, could have used either the child or the mother -- or both -- to force the husband to talk (“Talk, or we’ll shoot the lot of them”).

They did nothing of the kind; they never touched any of them. After searching the house and finding nothing, they announced that they were taking the husband in for questioning (very probably to confront him with the person who had betrayed him”). At trial, Mme Marceron recalled:

“ […] I asked him whether they would let him eat a little bit and get dressed. They agreed immediately. My husband then ate breakfast.

These men, accompanied by the Germans, asked if they could eat breakfast with him, telling me they would pay. I said: — If you want to eat, eat with my husband, just help yourselves” [PBL, 7, p. 53].

After eating breakfast, they left with the suspect. A French agent suggested to Mme Marceron that she give him her savings, in return for which, he would arrange to save her husband. ‘If you wish, he said, I’ll take this sum [200,000 F], and leave you with 25,000 F to raise your child. Yes or no?” (Ibid, p. 55, deposition of Mme Marceron). The woman agreed, and kept 30,000 F (p. 56).

A few hours later, M. Merceron returned and declared: “They knew everything. Mme Mesclos told them everything” (p. 57). He was, of course, obliged to reveal the hiding place of the explosives. The Germans deported him to Germany, but they left the mother in liberty and never touched the child…

At trial, moreover, Mme Marceron had the courage to finish her deposition declaring (before being interrupted by the The President of the Tribunal):

“I have nothing against the Germans. Of course, they’re our enemies, that’s obvious. A German defends his country, we defend ours…” [PBL, 7, p. 62, XXX “Merceron confesses”]

Such was the behaviour of the Gestapo towards the wives of Resistance members. This is very far from the image propagated by the official version of these events…

Introduction to Gestapo Articles

Summary of Gestapo Cases

Gestapo Legends

Post-War French Gestapo Trials

Conclusion