Chapters 6 – 10, pp. 110 – 199.

Illustrations by Edgar Lander.

VI

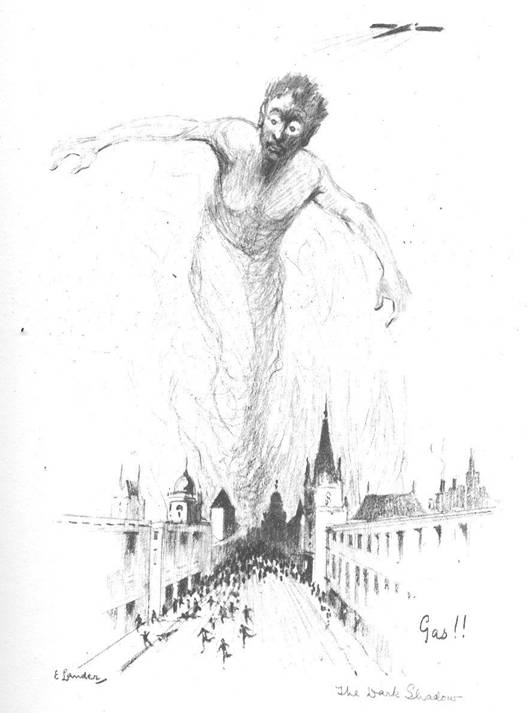

The

Dark Shadow

1

The Sense of Doom

IT IS IN THE MINDS of the English people—this

dark shadow. It creeps into English gardens where there is beauty and should

be, if anywhere, a sense of peace. It sits like a spectre

at dinner tables where there is good company, and if one listens, as I do, one

is conscious, very soon, of this ghost which haunts the minds of men and women

who have been talking amusingly and lightheartedly until, inevitably—at least

in the company I keep—the talk drifts, or lurches suddenly, into an argument

which begins with fear and ends sometimes with a laugh in which despair is

lurking.

I do not exaggerate or overdramatise. This dark shadow is caused by the dreadful

apprehension that by some inescapable doom we are all marching, against our

will, towards another war more frightful than the last—not the war to end war

this time but the war to end civilisation. That

shadow lies brooding over our English scene and

darkening all our hopes.

What is the use of this

"prosperity" proclaimed triumphantly by the government and by the

Press (ignoring the distressed areas and other less pleasant aspects of English

life) if it is going to be ended, rather soon perhaps (if one can believe the

same newspapers), by hostile air raids from some enemy unnamed, unless Germany

is named, smashing up our densely populated centres

and spreading panic and death by poison gas and incendiary bombs? What is the

good of this great scheme of physical training—the outcome of King George's

Jubilee Fund—if youth is only to be made fit for the next shambles? What is the

good of that Ten Years' Plan for Childhood, advocated by Lady Astor and her

friends, if in one year, or two, or three—1940 is generally named as the fatal

year by the prophets of woe—these children will be vomiting in gas masks and

huddling in cellars which are by no means bombproof?

"I want to frighten people,"

said Mr Duff-Cooper, secretary for war, anxious to

speed up recruiting.

Well, he has been doing his best, but it

was hardly necessary. Mr Winston Churchill had done

rather well in that direction by speeches and articles revealing the rapid and

vast rearming of

Up in

"Why are we working on day and night

shifts? Somebody seems to know something. It don't

look good, apart from work and wages."

2

Ways of Escape

One Sunday afternoon in the spring of this

year I went into two old country houses where pleasant people live, typical,

perhaps, of English life at its best. One belonged to a young doctor who had

been hard driven by the influenza epidemic and does not get much rest, anyhow,

in a practice which extends to many villages. He

looked tired, I thought, but was amusing in his conversation as he stood six

inches below the old black beams which go across his ceiling. But presently,

when we drifted into a talk about psychology, he asked me a curious question.

"Do you think young people ought to

escape from this lunatic asylum called

"Where would they go to find a

sanctuary?" I answered by another question.

"What about

He was worrying about that "next

war", perhaps on account of his young wife, perhaps as a theoretical

question nagging at him as he made his rounds, helping new life into the world,

attending to children and young people who might be caught by the fire of

Moloch.

It was strange that in the second house I

went to that afternoon there were two women who started talking to me about

this fear in their minds. One of them was the hostess of a tea party to which a

group of young, or youngish, people had come. We talked at the end of the room

for a few minutes and presently she asked me a question very seriously.

"Do you think that it might be wise

for anyone to get out of this country while the going is good—that is, before

another war comes? I've almost given up hope of peace. I'm sorry for the young

people—this little crowd, for instance."

It was the same question that the young

doctor had put to me. Behind it was the same sense of impending conflict. They

were both looking for a way of escape while there might still be time. It was

rather startling. It was tragic as evidence of a state of mind creeping into

English thought as a deepening shadow. All over

Another lady in the same room spoke to me

in a quiet voice. She had a little scheme in which, she thought, I might be

interested. Her idea was that a village like the one in which she lived, and

many others not enormously far from

That fear again! That

dreadful apprehension of a coming war.

I spoke quietly, as she had done, so that

no one could hear in a room where there was a cheerful murmur of general

conversation and occasional laughter. It was a good old house which for many

generations had belonged to farming folk but now was filled with a company who skim the latest books, and listen to the

wireless, and are in touch with

"I refuse to believe that war is

coming," I said sturdily. "It seems to me a kind of acceptance of its

certainty if one arranges plans for air raids and gas masks for children. That

is a surrender of all hope. It's putting emphasis onto preparation and not onto

prevention. War mustn't happen."

She was the mother of young children,

though young looking herself and beautiful. Reynolds and Romney painted women

like her. She looked, I thought, very eighteenth century in a long low room

with old-fashioned furniture.

"Besides," I said, "there are

nine million people in

"It might be worth while saving some

of the children," she answered.

Somehow, I thought, we must kill this

fear lurking in so many minds. How tragic, how farcical, how damnable, that

with all our massed intelligence, all our science, all our victories of civilisation, the minds of women should be haunted by this spectre of approaching horror for the children they have

brought into the world! Gas masks for babies? The very devil wouldn't think of

such abomination.

3

The Failure of the League

It was the breakdown of the

They had pinned their faith to the

principles of Collective Security. When Mussolini broke all his pledges to the

League, refused arbitration, and massed his troops for attack against the

Ethiopians, it looked, for a little while, as though the League would exert its

authority and put into combined action its clauses of restraint against a

nation judged to be guilty of flagrant aggression against any member nation of

the League. By Article 16 of the Covenant sanctions were to be imposed on

Mr Anthony Eden, that elegant young man representing

the British government, rapped on the table of the League Council. He took a

strong line, supported by his government at home. When Mussolini sent troops to

There was one day when I felt forked

lightning in the air—an oppressive atmosphere. Other people were aware of it.

It was a day when we were within an hour

or two of war with

Collective Security had a wide-open gap.

Only military and naval force—that is, war—could stop the Italian army on its

voyage to

The British Lion had roared and everybody

was much impressed. Then it began to curl its whiskers and wag its tail.

British prestige had been high.

There was an outburst of passion in

"It is not

Mr Baldwin came running into

It was all very dramatic. The voice of

"You needn't pay any attention to

these alleged Italian victories," I was told by an air commodore in his

drawing room one day.

He had just flown over

"The Italians make a little advance

and then have to draw back. It will take them years to

penetrate that country where black tigers lie behind the rocks."

"The Italian claims to victory are

all bluff," said a young American in the same room. He had just spent six

months in

Less than two months afterwards the

Italian army entered

It was a "glorious victory" for

It was one cause of that shadow which had

long been in the minds of European peoples—the shadow of fear over many

frontiers which now deepened and darkened. It reached

4

Hitler's

This Italian adventure gave a shock to Mr Stanley Baldwin, not easily shocked into any galvanic

activity until something "really must be done"—and to his advisers in

the Admiralty, War Office, and Foreign Office. The government was beggared now

of all slogans for the public soul. It was no use talking any more about their

faith in the League. The League had been badly battered and had gone into dry

dock for repairs, if possible. The Disarmament Conference had dragged along its

weary way to death. No use reviving that, they thought, wrongly, as I venture

to think.

Another menace, which seemed to them more

dangerous than

Some of the new leaders in

It was a kind of woolly Wagnerism applied

to modern life. They exalted physical strength, instinct, force, against

intellectualism and all the code of European culture derived from the Christian

faith and the Renaissance. The old tribal law of

The German people were being drilled

intensively. They were being subjected to an intensive propaganda which blared

into their ears, and into their minds, ceaselessly, under the direction of that

human talking machine Herr Goebbels.

Worse still, to the outside world, German

youth seemed to like it! They did not resist this discipline. They gloried in

it.

Visitors to

The intensive rearmament of

"When is this war going to break

out?" asked American people of a friend of mine named Curtis Brown a few

months ago. They were staggered when he answered cheerfully: "There ain't going to be no war!"

The English Press does not share his

optimism. Every day for the past two years many newspapers in

this country have kept their readers' nerves on edge. Every crisis

becomes to them a new threat of a world war. Every analysis of the world

situation leads them to the conclusion that war is coming nearer. Their correspondents

in many countries emphasise these constantly arriving

dangers. Politicians repeat dolorously that the international situation is

"deteriorating."

It deteriorated very intensively when the

Spanish Civil War aroused passionate emotion on the Left and Right of all

political groups. Spain became the Tom Tiddler's

ground into which half-a-dozen nations poured aeroplanes,

tanks, all munitions of war, and volunteers, for a trial of strength between

Democracy, as it was called, and Fascism, as it was called, though in that

tragic arena of blood, and heroism, and murder, and mercilessness on both

sides—a disgrace to civilisation, an outrage against

all Christian chivalry—there were many parties and many groups—on both

sides—which were neither one nor the other.

Labour and the Communists and the Left Wing

intellectuals clamoured for intervention on the side

of the

Is it any wonder that in the early part

of this year when England spoke behind closed doors, in old houses, in small

flats, in college rooms, in little restaurants, in clubs, and in

bed-sitting-rooms, there was a sense of fear that another war might happen and

that we were drifting to a calamity which would be the death of civilisation and the ruin of the Western world?

5

Who Wants War?

A man spoke to me on the stairs of a

Twenty-odd years ago this man, who now

has grey hair and sad-looking eyes because he is disgusted with the state of

the world, was a young officer in a Scottish regiment, and while he stood

talking to me his mind went back to a day in 1914. That was after a melancholy

remark he had made because of the dark shadow which was on his mind.

"We are all marching towards war,"

he said. "Who can doubt it? There's no ill feeling against the Germans.

They have no ill feeling against us. But we are being dragged into a state of

things which can only lead to another conflict. Democracy has no power over its

own fate; there is no such thing as Democracy. It's at the mercy of those on

top."

It was then that his memory went back to

a day in 1914, at Christmas time, when there was a truce between the lines, and

his men and the Germans went out into no-man's land to bury their dead and

started talking to each other. It lasted for three days, that truce.

"Do you want to go on

fighting?" asked this Scottish officer of one of the German soldiers.

He answered with the title of an English

song:

"Home, Sweet Home! That's all I want."

They all wanted that, on both sides. If

it had been left to them they would have stopped killing each other. They had

no enmity at all. They hated the war. They could see no sense in it. It was the

men on top who were going on with the war.

"This rearmament of ours," said

my friend, who used to be a Liberal M.P., "is a sign that we have

surrendered the

"Why not accept Hitler's offer of a

Western Pact?" I asked. "Isn't that the first step to peace in

He didn't agree. He thought it would be

playing

"But what evidence have we," I asked, "that

He hated Fascism. He had no faith in

Hitler's sincerity. But he groaned over the bill of costs for British

rearmament and its enormous folly, as he thought it.

"Think of what all that money would

mean in social services and productive plans! We could create a paradise. Now I

despair."

There were others like him in every part

of

One optimist took tea with me, a charming

man whom I met at the council table of the

"I wish you would write an

article," he suggested, "about the point of view of the younger crowd

in every country, showing that none of them want war. It would be a great

service, and I am sure you could get a lot of material from different

countries. It's only the elder statesmen who have got this war complex."

I made a few mental reservations. It was

true that even the young Nazis of Germany don't want another war. But they

would march with the exaltation of self-sacrifice if Hitler called them. What

about the young Italians?

And yet I believe he is right—this

distinguished little lawyer, Sir John Stewart-Wallace by name—whose heart flows

with the milk of human kindness and whose eyes reveal a schoolboy humour, in spite of his dusty lawbooks

and his legal dryness. The young people of

6

An Exhibition of Modern Culture

I dropped into an exhibition arranged for

public edification by the municipal authorities of Kensington, where once I

used to live.

Now, when I walk through Kensington Gardens,

I think of those peaceful days of my young manhood when I used to play with a

small boy on the coast of that Sea of Adventure—the Round Pond—where thousands

of small boys have watched their craft go out on distant voyages from which, on

days of dead calm, they never came back. Those small boys grew up just in time,

some of them, for a world war in which they were wanted, and they, too, so many

of them, never came back.

Those ghost memories were in my head when

I went through

By taking the advice kindly provided by

the Home Office and passed on to the municipality of Kensington, it was

suggested that precautions against this uncomfortable possibility should be

taken in advance—today or tomorrow, if possible—and that by a few little

gadgets—bits of stick, brown paper, gluepots and the glazed paper on cigarette

boxes or chocolate boxes—Kensington families might avoid all disagreeable

consequences of mustard gas or other varieties of poison vapour.

There was a little crowd in the

exhibition, including old gentlemen of Kensington who were very much interested

in this show and seemed to approve of its purpose thoroughly—"The nation

wants waking up!" said one of them—and a number of ladies from Kensington

Gore, Holland Street and Campden Hill (I guessed) who

seemed to accept this chamber of horrors as complacently as they would go round

Harrods to see the latest fashions.

"Most interesting!" . . .

"It seems to me very necessary." . . .

"Now, isn't that a good idea?"

. . . "So simple too! Really I think we must do

something about it."

There were rooms of small size,

representing bathrooms and bedrooms, converted into antigas

chambers. Bits of stick had been tacked onto the doorways and round the

windows. Wet blankets, or cloth of some fibrous stuff,

made antigas curtains. The very latest types of gas

mask suitable for Kensington ladies were exhibited on the tables. Lists of articles

to be kept in a gasproof chamber before an expected,

or unexpected, air raid were printed on big cards. They included domestic and

sanitary utensils, a screen, drinking water, biscuits, toys

for the children, playing cards for the grownups, and other items which might

agreeably pass the time while the enemy was dropping bombs. It was really all

very charming, to those whose minds work that way.

In charge of the exhibit were some young

women in Red Cross uniforms. I ventured to speak to one.

"Don't you think it might be better

to prevent a war rather than go in for this kind of thing?"

"Excellent idea!" she answered

brightly. "How are you going to do it?"

"Doesn't this seem to you a

surrender of reason?" I asked this good-looking girl with very steady eyes

which looked frankly into mine.

"An acceptance of war, do you

mean?" she asked. "Yes. That's how it seems to me."

"There's only one kind of defence, really," she told me, looking over her

shoulder as though she might be overheard; "that's by retaliation. I

suppose if we're strong enough to retaliate we shan't be attacked. Isn't that

the best hope?"

"What's the good of all this

nonsense?" I asked. "Do you honestly think it's

any good at all?"

She was very honest.

"It might save a few. That's better

than saving none."

I wanted to have further conversation

with her. She reminded me of a girl I had known before the war and in the war,

a very brave young woman named Dorothy Feilding who

had helped the wounded lying on Belgian battlefields, quite regardless of her

own danger. This Red Cross girl would do the same kind of thing, I thought, in

the streets of

So this, I thought, as I wandered round

alone, is what we are coming to! What a beautiful revelation of the civilisation we have reached in this year of grace! What a

lovely introduction to life for young children who are to be instructed on the

wearing of gas masks, instead of reading fairy tales, and who are to be told

that in a year or two they may have to take their dolls into a blanketed room

to escape from a poisonous breath creeping through the streets, while millions,

who are unprepared, choke to death or are burnt and blistered! There will be

the crash of heavy bombs, destroying many houses and burying their inhabitants

under their ruins. There will be incendiary bombs, dear children, making

bonfires in the sky and roasting thousands of people in their flames. You see,

darling, the nasty Germans want their colonies back, but if you are very good,

and wear your gas masks nicely, and play in those comfy little rooms with their

cracks pasted up, our dear Lord will look after you, and possibly let you

remain alive and see the ruins afterwards. Won't that be nice?

Great God! I thought, going round that

exhibition in Kensington. So this is the best that mankind is doing with its

intelligence! This is the latest exhibition of our Brave New World! Without any

poison gas, I felt poisoned.

And a few days later I read a report

about these Home Office recommendations for air-raid precautions. It was by a

number of scientists at

The experimenters, who included two

women, converted four rooms—shop basement, villa dining room, council house

sitting room, modern bathroom—into gasproof rooms

according to the official handbook.

They found that gas penetrated bricks and

plaster, cracks covered with brown paper and mushed

paper, blocked-in fire-places and sealed doors.

In one room gas, which outside would kill

in two and a half minutes, would kill inside within ten.

In the bathroom—with steel-framed

windows, tiled walls, concrete floor—gas would penetrate and kill within four

hours.

Then they tested incendiary

bombs—classified as a greater danger than gas or high explosives—and found that

the sand-spreading advised was useless.

Welding thermit, a comparatively mild incendiary compound,

defied all such efforts, burned under water, through metal, through sand,

through floors.

"If we take a specimen raid of nine

bombers, each carrying a thousand small bombs, nine thousand could be dropped

on an area of two square miles.

"Allowing that in an urban area only

a fifth of these cause fires, that means 1,800 fires.

The danger of fires spreading over several blocks of buildings, making the

centre of the conflagration quite unapproachable by fire brigades, is obvious.

"On hearing the warning people will

rush to their gasproof rooms, and then when

incendiary bombs set fire to the upper parts of their dwellings they will

either run out and be caught by the gas or stay inside and be roasted alive.

"This is how they would act if they

follow the instructions of the Home Office."

Gas masks tested were found useless

against mustard gas and lewisite.

Protection for tiny children is shown to

be impossible, and the report pictures children, sealed up in containers,

screaming themselves into fits, with the mother trying to pump air to several

at once.

Would fathers and mothers protect

themselves and watch their children suffocate? they

ask.

The full absurdity of all this is shown

by a criticism of the Home Office advice: "Set aside a room in your house."

In

So 8,669,000 would find a gasproof room impossible.

As for evacuating big cities by train—a

few bombs on the termini would stop traffic for days.

We had better concentrate on stopping that next war if possible, for if it

comes, retaliation is no protection.

Those

Who Wear Wings

1

One of Our Air Pilots

I WENT to tea at a house in

It is like a country mansion with big

rooms and big open fireplaces where, in winter, logs are burning. In summer the

sun—if there is any sun—streams through the casement windows, and there is a

garden behind the house with a lawn smooth and large enough for croquet, which

the mistress of the house is pleased to play with her friends. Birds sing in

the bushes. Once, I swear, I heard a nightingale, though if one has listening

ears one hears very faintly the murmur of

At that tea table, round which we sat in

a homely way—there were some nice hot cakes thereon—I noticed two youngish men

whom I had met before. They were, as I knew, "those who mount with wings

as eagles." That is to say, they were pilots in the Royal Air Force.

There were some women at the table and

laughter touched our talk. It was all very pleasant and very comfortable. This,

I thought, is what civilisation means at its best: a

pleasant room, a cheerful company round a tea table, conversation which is

merry and open minded. One would not have to put a guard upon one's tongue, as

one has to in some countries nowadays, or be afraid to express one's ideas on

any subject which comes into one's mind. This was Liberty Hall.

One of the flying men sitting on my right

picked up some phrase of mine. I have forgotten what it was, but I have an idea

it was something about a recent visit I had paid to

"I suppose you know we're living in

a fool's paradise?" he asked, with a queer ironical smile. "This

country is in considerable danger, and nobody seems to know, and nobody cares a

damn!"

He said something like that and there was

an intensity in his voice which startled me, and a

look in his eyes which I could not misinterpret. It was the look of a man who

has something desperate on his mind.

"Don't you pay the slightest

attention to him," said my hostess. "He has been trying to frighten

me. If I believed a word of it I shouldn't be able to sleep a wink."

"No, no!" said the young

airman, laughing good-naturedly, but a little uneasily, perhaps. "I'm not

a scaremonger. But I hate eyewash and a false sense of security."

"Have another toasted bun,"

said the lady.

He had another toasted bun. The

conversation went round the table in a lighthearted way. But I knew that the

boy on my right was seething with something he knew and didn't like.

After tea four of us—all men—went into

another room where there was another fire. They were the two young flying men

and my host and myself. Three of us lit cigarettes.

"Did you see anything of what they

were doing in the air in

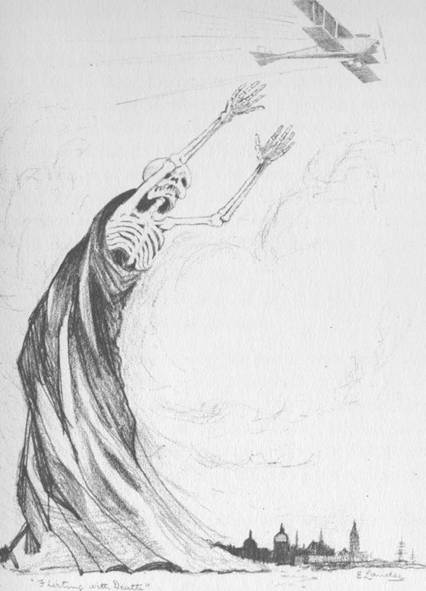

FLIRTING

WITH DEATH . . . .

I hadn't seen much of a technical kind.

But I had spent a little time at the Flughaven near

And I remembered a journey I had made

through

Lift Up Your

Eyes.

Our Future Is in the Air.

Help German Aviation.

In

The flying man threw away his cigarette

and spoke quietly but with a kind of restrained passion.

"

At that time it was distinctly

unpleasant. We were still at cross-purposes with Signor Mussolini. Our prestige

had fallen to a low ebb.

The flying man thought it abominable. The

"I'm not an alarmist," he went

on, "but I suppose you would agree that some damn silly accident might

happen, some combination of bandits might make trouble, or war might be forced

upon us to defend vital interests.

I hated to think so. It would be the end

of everything which we find good or endurable.

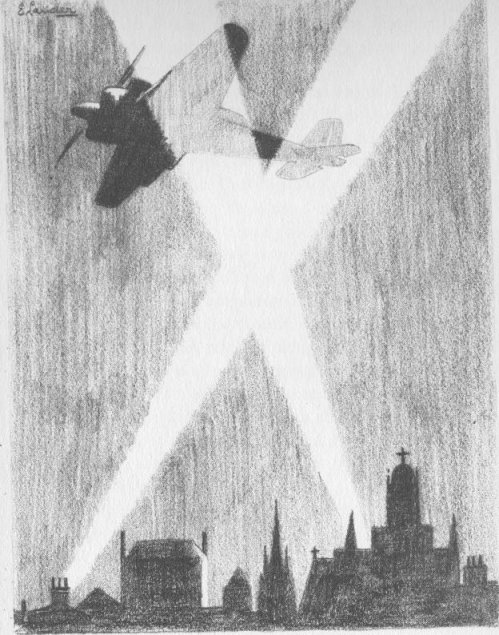

"If war happened," said my

flying friend, "it would come suddenly, perhaps without an ultimatum.

German bombers would appear over

He looked me in the eyes and said

something which made me feel rather cold, although the fire was still burning

on the big hearth.

"We have no defence

and no means of retaliation." I couldn't believe that and told him so.

"What about our expansion scheme?

The white paper! All this rearmament! Aren't we vastly increasing our fighting

force in the air?"

The young airman laughed bitterly.

"Official dope! The expansion scheme is mainly on paper. It's faked arithmetic, put out by the Air Ministry to keep

the nation lulled to sleep and ignorant of its appalling dangers. The higher

control of the Air Force are the cause of all this mess, and their main

preoccupation at the moment is to cover their past failures and deficiencies.

Their concealment of these facts can only be done by going on with concealment.

Men who have failed in the past—blind to the technical and tactical problems of

air-fighting—go from important to more important posts, and this line of

inefficiency continues without a break. Hopeless!"

He looked across at the other aviator.

"Am I exaggerating at all, do you

think?"

The other man shook his head.

"The painful

truth! Every experienced pilot

knows it perfectly well."

The boy who wanted to get these things

off his chest was silent for a little while and then sat forward in his chair.

"

He uttered another alarming sentence.

"Our Air Force can't strike a blow

of any kind at

The two air pilots went on talking.

2

A Grave Indictment

It was a terrible indictment which

afterwards I heard from other sources of information. The present situation

reveals that technically we haven't the aircraft, equipment or organisation which would give us the power we should need

in another war. There is an appalling dilution of skilled personnel by hastily

trained learners. Our biggest bombers have a short range, and are so slow

compared with aircraft possessed by other nations that they couldn't hope to

survive a long flight across hostile country, and do not possess the air

endurance, at any endurable speed, to permit of them operating from home bases

into a country as far away as Germany. The increase of the Air Force is based

on the production of machines of these old-fashioned, slowgoing

types of bombers.

"If we have a war forced upon us in

the next few years we shall be powerless to retaliate in the air."

My host looked very grave but kept

extraordinarily silent. I wondered about all this. I could hardly believe it.

Perhaps the man who did most of the talking was fanatical on some theory, or

disgruntled for some personal reason, or obsessed by the fear of a German

menace. There was no doubt in my mind about the last point. He had no faith in

German peace-mindedness. Me gave them about two

years—if that—before they strike. They were just playing for time, he thought.

We should have to play for longer time than that, and even then we should be no

match for

All this must be taken with heavy

discount, I thought. This flying man is exaggerating his case and not making

allowance for the government's plan of development. Anyhow,

I left the house where those two airmen

had been talking, and had a sense of dark doubt. I didn't believe in piling up

armaments as the way to peace. I was a

"We have no means of defence. Our Air Force is incapable of striking a blow

against

"What's the matter?" asked a

friend of mine whom I met on the way home. "You look as if you had heard

bad news. Worried about something?"

"Worried about human

stupidity," I answered. "This planet is not governed by intelligence.

We're all going stark raving mad again."

He was very much amused.

"We've never been sane," he

answered cheerfully.

3

There Is No Defence

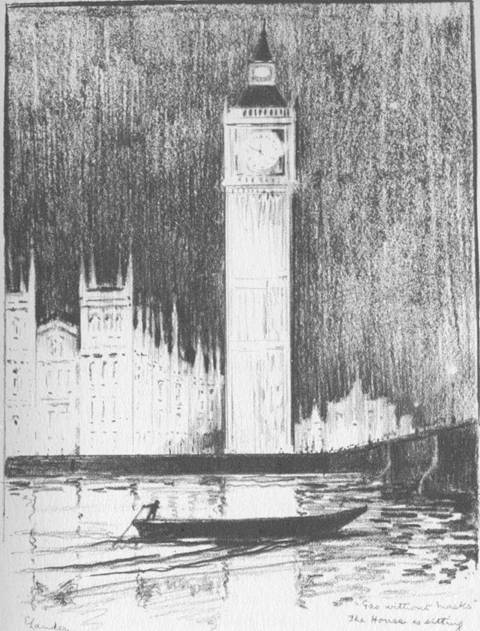

I listened to a debate in defence in the House of Commons. Mr

Winston Churchill, the right honourable gentleman

below the gangway, as they called him, sat making notes while the talk went on.

Presently he stood up and attacked the government for delays in expanding the

Air Force. The government programme and pledges, he

said, had broken down completely. We had been promised parity with

As I listened to this debate I looked

down upon the members of the House and the two front-line benches where

ministers and ex-ministers sat in various attitudes of mild interest or mild

boredom. The government men and their supporters, with few exceptions, seemed

satisfied with Sir Thomas Inskip's report of

progress. There was no sense of national danger sufficient to disturb their

placidity of mind. They seemed to accept the inevitability of delay as though

there were lots of time ahead, anyhow. Churchill's portentous phrases were what

they expected from him but did not make them turn pale or hear from afar the

noise of wings over

All this had only touched lightly upon

the difficulties and delays in expanding our Air Force. But after that debate I

came into possession of facts—they seemed to me reliable—which revealed the

reasons why the young airman with whom I had taken tea one day had no touch of

breezy optimism but was gravely anxious. Those facts were given to me, I

suppose, because I might have the power of the pen to stir up the nation to a

sense of its unprotectedness in the air and to bring

pressure upon the government to awake from its stupor. Those who were my

informants acted, I am certain, from a high sense of duty to the nation and were ready to sacrifice their own careers that the truth

might be known. The whole truth is not yet known, though some of it was exposed

and admitted in another debate of the House on January 27 of this year.

Sir Thomas Inskip

acknowledged very frankly that the original plan calling for the provision of

71 new squadrons of 12 first-line aircraft in each squadron, making 124 in all,

had broken down in the timetable. Only 87 squadrons had so far been formed,

though he anticipated that 100 would be reached by the end of March of this

year. The remaining 24, "or at least 20," would be ready by July of

this year. But not all of them would be real squadrons but only skeletons of

one or more flight each, and Sir Thomas was not able to say that by that time

they would be brought up to their full complement.

Mr Churchill urged that there was an enormous

percentage of deficiency. If 124 squadrons were completed by March 31 it would

still not give us parity with German strength at that date, nor

anything like it. We had been solemnly promised that there should be parity. We

had not got it. We had no right, he said, to assume that any quarrel would

arise from

The debate put many cards on the table

which had been held back, but by no means all of them. Many of these had been

placed before the prime minister in a secret report by Mr

Churchill, who found himself in the position of having a mass of information of

an alarming character, as to lack of efficiency and failure in the very basis

of planning and design, which he could hardly publish to the world without the

revelation of secrets which might encourage potential enemies.

Curiously enough, I found myself in the

same position. I had notes of a very technical and secret character which

seemed to me too important to ignore or hold in my own knowledge. They were a

grave indictment of official complacency, official inefficiency, and of a most

distressing state of things in the Royal Air Force which would endanger the

lives of our young pilots in time of peace and lead to inevitable disaster

should there be war. But I could not bring myself to publish them in the Press

in a series of scare articles. I decided to put them into the hands of the man

who had taken up this subject and made himself the spokesman of the case for a

strong Air Force. That was Winston Churchill, who might care to have my notes,

though I might be "carrying coals to

Meanwhile, in many countries—Germany,

France, Italy, Russia, Japan, the United States—there was at the beginning of

this year a ceaseless endeavour to increase the

numbers of fighting aircraft, their range, their speed, the bomb-carrying

capacity, and the number of their trained pilots and crews. The Civil War in

manhood, womanhood and childhood in

But what alarmed me most about the

criticisms of our air efficiency was the awful thought that all this

intensification of armament, now being carried out by our government, may be

controlled by minds like those which were in charge of our war machine in 1914.

Those minds of cavalry officers, promoted to high command by social pull, good

looks and the camaraderie of a caste, were not exactly inspiring of confidence

among the men who were condemned to die in a World War. The official history of

the war does not break down the suspicion that they were unequal to the job in

hand. Is there any new assurance that the men who are now in high command—in

the Air Ministry, for instance—are of a different mental calibre

from those who were Brass Hats in

That is rather frightening.

VIII

The

Red Dream

1

A Russian Fairy Tale

ALTHOUGH in

I once tried to read that book and found

it very difficult and dreary. But other people who have actually read it—most

of those who worship at the shrine of Karl Marx have not read it—think it

wonderful. Professor Laski, for instance, thinks it

wonderful. I was dining opposite to him one night in a private party and he

made a statement which astonished me.

"Before I studied Marx," he

said to me across the table, "I could get no real basis of political and

economic philosophy, but I found his work extraordinarily stimulating, and it

gave me for the first time a sense of optimism."

I confessed that my unsuccessful endeavour to master Das

Kapital had left me with a sense of profound

gloom. For as far as I understood the main thesis of the author, it was that human

society was moving towards an inevitable class conflict, because under

Capitalism the poor were bound to get poorer and the rich richer until that

immense gap caused a break of the whole system which would be followed by the

dictatorship of the proletariat.

The old gentleman in the white whiskers

and a Father Christmas beard was the apostle of the Class War. That doesn't

seem to me a cause of joy. Yet one has only to look around one's own country,

and others, to see that, apparently, his prophecy has not come true. Here in

They have what seems to me a fairy tale

in their minds. It is untouched by reality or by the cold evidence of truth. It

has its origin in

I was struck by that one evening when I

was invited to dinner by a charming friend of mine who "threw a

party", as they say in the

Charming young men, I found them. One of

them had just written a book on

I did not intervene in this discussion.

My knowledge of Russia is becoming distant—as far back as the days when

twenty-five million people were starving (four and a half million died on the

Volga), when everyone in Russia was hungry, when millions were dying of typhus.

Perhaps things had improved since then. Some of these young men had been

recently to

Did they honestly think that the

condition of the Russian people was higher than in this country where they sat

at table talking freely? Did they believe that liberty was there—any kind of

free thought or free speech? Did they still believe that there was equality of

class and equality of reward? Had they not seen the well-dressed and well-fed kommissars at the Mariinsky

Theatre with their bourgeoise-looking women, and the

Russian peasants, or labourers in the timber camps,

not well dressed and not well fed, but miserable, and verminous,

and hungry? Why this admiration for the mechanisation

of Russian life—and the herding of peasants into collective farms, and the

crowding of the sky with bombing aeroplanes, and the

iron discipline of the ant heap? They used the words "Democracy" and

"

No doubt in

2

Intellectual "Reds"

At another party given by the same

charming young friend of mine I sat opposite a man who is known throughout the

English-speaking world as a fine scientist and thought-provoking brain. He

dreams in Latin and is delirious in Greek. Presently he began to talk about

Karl Marx, and the Russian revolution, and the creed of Communism. He seemed to

see something fine and noble in what to others, like myself,

appears to be a denial of intellectual liberty and the tyranny of Terror. This

scientist, by some trick of the brain, was able to ignore the agonies and cruelties

which have gone to make this Russian experiment of a new social system, or to

weigh them lightly in the balance compared with agonies and cruelties inflicted

on mankind by capitalism. He has persuaded himself that the results have

justified all that suffering—results which appear in that low-grade civilisation now existing in Russia, that discipline of

human ants, that tyranny of Cheka and Ogpu.

What is the mystery, or the secret

vision, which causes such a mind as this—it belongs to Professor Haldane—to worship at the shrine of Lenin and pay homage to

Stalin, that man of steel and blood? Professor Haldane

has the courage of his convictions. He went to

And yet Professor Jack Haldane has a fine brain, a gay humour,

and, I am certain, a kindly heart. Other brains not so high as his, but quite

intelligent—our little intellectuals—are seeing Red and dreaming Red, though

they have never read Karl Marx nor walked across the Red Square below the

Kremlin walls. They do not seem to know that Communism has been abandoned,

largely, in Soviet Russia, which now has inequality of class and wages, recognises private property and the right of inheritance,

and has established a corrupt and mean bureaucracy above a mass in human

bondage.

3

The Ardent Mind of Youth

This Red dream touches the ardent mind of

youth, here and there, in universities, training colleges, and

bed-sitting-rooms. Undergraduates of

One of them—the son of an old friend of

mine—honoured my wife and myself with a visit and was

good enough to take tea with us. He is a very handsome young man with dark

dreamy eyes in which at times there is a gentle smile. A poet, one would

TERROR

BY NIGHT

say at first glance. But we didn't talk of poetry

that afternoon. We talked of something more dangerous even than poetry. We talked

of Communism.

He is a very intellectual young man and

one of the leaders of the Extreme Left at

My wife and I gave the young man a fair

innings and listened with amiable consideration. He did not believe in

tolerance, he told us. Tolerance meant acquiescence in injustice—such as in the

distressed areas—and the cruelties of the Capitalist system, which of course,

he said, was beginning to break down everywhere. The younger people of his

crowd looked forward to the end of all that by direct action and the removal of

the old dead-heads. Old age, he thought, had been too long in power. It wasn't

their fault, of course, but their minds were incapable of moving forward and accepting

any other system than the one into which they had been born.

"Everybody over the age of

forty," said this humane young man, "ought

to be shot."

My wife and I glanced at each other. We

were, alas, over the age of forty.

"Their minds are too rigid," he

explained gently. "One has to realise that

nothing can be done in this country until that generation is safely dead. Then

we can get busy, shaping things differently. Of course there will have to be a

fight, anyhow. I am not one of those who believe that the system can be changed

without bloodshed. Vested interests, the defenders of Capital, the diehard type

of mind, the Fascist spirit, which is latent in snob minds, will have to be

defeated—and they won't surrender without a struggle. I shall live to see the

day when the barricades are up in

"Supposing," said my wife very

quietly, "that I happened to appear on the other side of your particular

barricade? What would you do?"

Our distinguished visitor—that charming

young man—took another piece of cake and flicked a crumb from his knee. "I

should shoot you," he said sadly but firmly.

It was an interesting conversation. I

wondered how many followers this young man had at

"It's quite all right," he said

in a kindly way. "You can't help it. You're one of the old Liberals, of

course. You belong to that era."

I belonged, in his mind, to the damned

dead past.

4

Impatience of the Younger Mind

These young intellectual Communists are

not to be taken too seriously, although they are influencing other minds,

especially if they become schoolmasters and writers after college days.

What is the lure to them in this creed

which, in every country where it works, leads to civil strife, murder and all

cruelties? Is it due to a twisted morality in their minds? Is it some subtle

poison of the brain? I think that among the younger intellectuals it is due to

generous instincts—hatred of injustice, pity for the underdog, impatience with

the slowness of social reform under parliamentary government, and disgust with

the insincerities of the political game.

That emotion of sympathy with the

down-and-outs, or the populations of the distressed areas, overwhelms their

judgment and their sense of proportion. Because half a million people or so in

this country are living in poor social conditions—which are getting better—they

see red and are willing and, indeed, eager to drag down forty-eight and a half

million people to the same equality of squalor. Because Parliament is incapable

of rapid action, and the government twiddles its thumbs on the Front Bench

while flagrant abuses cry out for redress, they ridicule the parliamentary

system and proclaim the blessings of Soviet rule and the need of revolutionary

action.

I can understand this impatience of the

younger intellectuals. They went out to hear the stories of the Jarrow marchers and were angered. I don't blame them, for Jarrow is not a pleasant story, anyhow, and is no credit to

a Conservative government, which, year after year, has left the men of Jarrow without lifting a finger to give them a chance of

work. They played into the hands of sinister interests who blocked the only

scheme—a new steel works—which would bring back life

to Palmer's Yards.

Even when the armament industry was in

full blast, with rush orders, and arranged to lay down new steel works, it was

not at Jarrow but at

As the mayor of Jarrow,

in great indignation, wrote to The Times:

The Government's policy towards

the Special Areas is a curious one. Surveys, Special Commissioners, public work

schemes are all to the good, but surely these should be mere preparation for

the introduction of permanent industry. On the eve of the introduction of a

Government Bill in Parliament to deal with Special Areas we read, only six

months after the Jarrow scheme was turned down, of a

new steel works in a small Lincolnshire town (which is not in a Special Area)

which will employ between 2,000 and 3,000 more men than are employed at the

present time.

These men will

presumably be expected to come from other centres,

leaving behind them a waste of social capital and necessitating doubtless the

building of houses, roads, schools for their children, and other public works,

and the provision of public services which they leave behind, whence they came,

to be wasted.

That kind of thing makes men see red,

even though the red dream is an illusion in its fairy tale, and here, if one

tried to make it real, would lead to a river of blood and irredeemable ruin,

more even than in Russia, which is less finely balanced in its social mechanism

and more firmly planted on the soil.

Other voices call to the young

intellectuals of our universities and to students in their bed-sitting-rooms

where they look up from their books and hear the murmur of life in the streets;

or go to a window and look across the chimney pots, and wonder It the meaning

and mystery of life which they have to face and try to understand.

How is it, they ask, that there are so

many anxieties pressing down on individual lives? There is no sense of

security, no certainty of getting a job, even if an underpaid job. How can a

man fulfil his life as nature intended? Where is his

mate? How can he afford the luxury of love? He is shabby, overworked, uneasy in his mind, out of tune with life itself. Perhaps

Marxism makes things easier, he thinks. In return for service to the state a

man gets his food, clothes, amusements and lodging. No nagging landladies

demanding arrears for lodgings. No class distinction of dress and snobbishness.

No sense of insecurity. Free love, even if there is no free speech. A level of

equality with one's fellows, without the damned injustice of prodigious wealth

garnered into a few hands—the manipulators of money, the masters of machines,

the Merchants of Death, the people with a pull, the jugglers with bears and

bulls, while the mass of the population lives in dreary drudgery not sharing

the fruits of their own toil. This Capitalism?

"Oh, God!" cries the young intellectual, who doesn't believe in a

deity but feels very moody on a Monday morning or inflamed with intellectual fervour on a Saturday night after three cocktails in

another fellow's rooms. I can understand all that perfectly! As

a French writer has said: "A man who is not a Marxist at twenty has no

heart. A man who is a Marxist at forty has no head."

5

A Young Man Thinks

There is another reason why the young

intellectual has leanings towards the Marxian ideal. His people at home look

alarmed when he talks about it. It amuses him to alarm them.

His father is an instinctive Conservative

and doesn't want a damn thing changed. He even grouses about the new buildings

in

Then there is this menace of war. The

young intelligentsia does not wish to be caught in some mantrap and blown to

bits by tempered steel because Mr Stanley Baldwin

says "our frontier is on the Rhine"; or because Mr

Eden is playing a game of jigsaw puzzle with Mussolini on one side and M. Blum

on the other; or because Herr Hitler has a grudge against Czecho-Slovakia—where

is it on the map?—or because, having piled up a lot of armaments at great

expense, it seems a pity not to use them with the blessing of the Bishop of

London.

What is the good, asks the younger mind,

of reading, thinking, scheming out a good life, working for the love of a nice

girl, getting interested in art or music, when, in a year or two, Fascist

bullies, or Colonel Blimp, decide to have another world war—or something slips

by accident and makes the big explosion, to the astonishment perhaps of those

who have been hoarding high explosives? That was the kind of question which

caused a number of young gentlemen at

The H. G. Wells young man—1937

edition—reads the News Chronicle or the Daily Herald. Perhaps he

goes up the

Perhaps here is the clue, thinks Mr Kipps, to international

comradeship across all frontiers. The United Workers of the

World. The Dictatorship of the Proletariat. The

working classes don't want war, he is sure of that. They don't want to have

their bowels torn out by high explosives for some war arranged by a competition

for markets between Capitalist nations. Perhaps the class war, he thinks, will

have to happen first, before that union of democracies conducting their affairs

by co-operation, and reason, and a sense of human brotherhood. The class war!

Not too pleasant if it happens, of course! Karl Marx said it was inevitable.

Perhaps Fascism and Black Shirts would win first. What about

6

A Gruesome Show

In

It was a gruesome show and not quite fair

to Russian development since the early days of the revolution. Here were

ghastly photographs of the starving children such as I had seen on the

Perhaps some of that has died down now. I

was talking to a young Russian who told me that all over

What interested me most in this

exhibition was the portrait gallery of the revolutionary leaders in the time of

Lenin. It looked like a rogues' gallery. They had dreadful, almost inhuman,

faces, some of these men. They were like masks out of which stared dead eyes.

Perhaps the camera had not been flattering. Radek,

the editor of Pravda, now in a prison cell, was very ugly, with a fringe

of reddish hair round his flat face, but he had humorous eyes when I sat

opposite to him in the Kremlin, and was not so

frightful as his portrait here.

This room in

In that exhibition one saw nothing of the

new

He would often be underfed. He would be

spied on. He would live in filthy conditions with filthy food. He would see

around him a mass of misery and the disease of vice even among young people.

A wet wind was blowing on Tower Hill, and

scudding clouds seemed low over the old Tower itself. About a thousand men, I

guessed, stood about in small crowds on this open place during

THE

ORATOR ON TOWER HILL

7 Free Speech on Tower Hill

the lunch hour. They were grouped round different

orators, each of whom was competing for an audience by his special brand of

political conviction. One man dominated the rest, standing higher than the

others on a raised platform and shouting louder. He had the biggest crowd and I

hadn't been there two minutes before I knew that he stood for the Spanish

Government of Caballero against Franco and his Fascist allies. He stood for the

United Front, the Clenched Fist, and the right of free-born Englishmen to fight

for Democracy in

Before I bent my attention to his

argument I had a moment with old ghosts. For I was on ground

once soaked with the blood of Englishmen who had died, by axe, or rope, or

fire, for conscience' sake, for freedom of faith, or for their own intolerant

fanaticism. Over there in the

In

Two City policemen, big beefy men, stood

with their backs to a wall watching the crowd and the speakers but not

listening. They were there in case of a row. They were not there to check the

flow of eloquence, however fiery or foolish. They were chatting together about

professional incidents, one of which seemed humorous and caused a laugh to pass

between them.

The crowd was made up mostly of city men,

office boys, packers, porters, warehousemen, and such like. Where I stood on

the edge of one group a sturdy middle-aged man, with a scarf instead of a

collar round his neck, was eating monkey nuts industriously, and round him was

a litter of empty shells. An old woman in the centre of the Hill was serving at

a little chocolate stall and did good custom among spectacled office boys who

had come here in their luncheon hour for an intellectual feast while they

munched a few biscuits and sucked those sticks of chocolate.

The young man who had attracted the

biggest audience was a tall, thin, muscular fellow with an Irish-looking face,

gaunt and hollow eyed, with a shock of dark hair through which almost every

minute he thrust both his hands with outspread fingers, as though to let his

thoughts escape more freely from his hot head. He had a good voice which came

from his stomach, as it should, instead of from his throat. His words rang

across Tower Hill.

"

It seemed to me curious that a Communist,

as I guessed him to be—certainly an orator of the United Front—should show such

zeal for the British Empire, which in the past they have so often denounced for

its "brutal Imperialism." But his hatred of Fascism was so intense

that he was willing to appeal even to the imperialists to defend the

anarchists, syndicalists and Marxists in

His voice rang out over the heads of the

crowd.

"We boast of our liberty, but is it

not an outrage against liberty that

"What about shooting civil prisoners

in

For a moment the orator high above his

audience listened to this heckler in the crowd. He laughed scornfully.

"This gentleman talks about the

shooting of prisoners in

"You're a liar," said a man in

the crowd.

There was a slight dispute on this point.

It took the form of a heated conversation in the crowd itself.

"He's a liar," said one of

them. "He isn't a liar," said others. The orator thrust all his

fingers through his dark hair and took a breather.

"This Spanish Civil War," he

continued after that respite, "seems remote from

He spoke well and interested this

audience of city men, porters, packers, warehousemen, and casual labourers.

I joined another group gathered round

another orator. Several office boys were listening to him with giggles and

goggle eyes. The man who was eating monkey nuts was among his audience,

standing among the shells. Squarely in front of him stood a well-dressed man

who looked like a city clerk from one of the outer suburbs, and he interrupted

the speaker from time to time in a polite and argumentative tone.

At first I could not quite make out the

drift of this speaker's thesis. He was a Highland Scot, I should say, judging

from his way of speech, and he had a lean face, with dark eyes and heavy

eyebrows.

"What about the love of a woman for

a man?" he was saying as I drew near. "Oh, very

romantic! And I don't deny that there is such a thing. A woman will love

a man—a man will love a woman—certainly. It's human nature. It has happened in

history. It happens now. Married or unmarried, it makes no difference to love

or loyalty. But when they get married what happens? The wife says, 'I want

another shilling out of your wages.' The man says, 'I can't afford it, old

girl.' She says, 'You've got to afford it.' That's when love flies out of the

window. Why do women marry? For security and a man's wages.

This marriage business is the cause of man's unhappiness and woman's."

"But your theory of companionate

marriage," said the man in the crowd, "what happens to it in the case

of a child coming?" I caught the drift of it now. That lean cadaverous

fellow was an advocate for free love.

"In any case," he said,

"there wouldn't be a child. I wouldn't take the risk of bringing a child

into the world in its present state—with a war coming along pretty damn quick,

and Capitalism arranging another Massacre of the Innocents. No sir! there would be no offspring of a six months trial. I say six

months. In that time a man ought to know whether the woman suits him for

keeps."

"But, Mr

Speaker," said the man in the crowd earnestly, "accidents will

happen, you know, in spite of your theory about rigid birth control."

"Wise people know how to deal with

accidents," said the speaker. "I'll say no more about that! My point

is——"

"But, Mr

Speaker," said the city clerk—as I took him to be, "if everybody

acted on your theory there would be no population at all. If nobody had

children——"

"Well, I haven't made as many

converts as all that!" answered the dark-eyed man, twisting his lean jaws

to a frightful smile. "There will always be mugs. In any case . . ."

He had a grudge against Capitalism. He seemed

to think that the support of family life was one of the forms of

"dope" handed out by Capitalists to the starving proletariat to keep

them enslaved.

"Family life!" he exclaimed

scornfully. "Now, I ask you to remember your own family life. Was it a heavenly

state, or was it damned disagreeable—a hell on

earth—with family squabbles and family rows, and family tyrannies? What about

the time when Ma is in one of her tantrums? What about those days when Pa laid

down the law about staying out late or bringing home one's lassie? Family life? My God!"

One of the office boys sucking a stick of

chocolate thought this extremely funny and giggled. He was enjoying his lunch

hour prodigiously. But I wondered if it were quite good for this

lad listen to a discussion on birth control by a man who was trying to

undermine family life on the Russian model. But there is free speech on

Tower Hill.

I turned my steps towards another group.

They were being addressed by a middle-aged man who belonged to some anti-Socialist

league. He was in the middle of a quarrel with four or five men very close

below him. Their heckling had made him angry.

"I demand free speech!" he

shouted. "If you men come here you ought to give me a decent hearing.

I'm trying to tell the truth. If you don't want to hear it others

do."

"It isn't the truth!" said one

man below him. "You're a dirty liar."

"And you're a supercilious

fool," retorted the speaker. "You have no manners. I don't

object to a reasonable amount of heckling but I won't stand for coarse

abuse."

"You began the abuse," said the

man below him. "You called me a cad. Now you call me a fool. You

ought not to be here. You're just the paid agent of maiden ladies who are

frightened of democracy. It makes me sick to listen to you."

"Gentlemen!" said the speaker,

ignoring these last remarks and addressing the general audience, "on this

Tower Hill there is the tradition of free speech on all sides. It is a

valuable heritage. You see that it is denied to me and obstructed by those

who mouth the word 'liberty' and under that name try to spread

the poisonous doctrine of Lenin and his Russian colleagues.

The recent trials in

"Keep

8

The Communist Party of

Is there any real danger in this Red

stuff which is being given as food to babes by Mr

Harry Pollitt—that mild-mannered man who appeared

before the Royal Commission on Arms—and his fellow members of the Communist

party of Great Britain? Their own membership is something over eleven thousand,

which isn't much in a population of forty-nine million. But they and other Red

bodies do a considerable amount of quiet propaganda, in factories and arsenals

and dockyards and barracks. It is partly paid for by subsidies from the Russian

members of the Third International, called the Comintern.

According to the Communist party's own reports in a leaflet quoted by the

Anti-Socialist and Anti-Communist Union, it received in the first two years of

its existence from outside sources £61,500, and from internal subscriptions

£699. From the same source I quote another extract.

Mr Fenner Brockway,

secretary of the Independent Labour party—one of the

bodies which has recently agreed to form a United Front with the

Communists—wrote to the New Leader as follows:

The payment of subsidies

to national Communist parties by the Commintern makes

them the obedient instruments of the Russian Communist Party, which contributes

predominately to the Comintern Funds. Take the

position of the British Communist Party. Probably 70 per cent of its

membership is unemployed. Yet the Party runs a daily newspaper and an elaborate

monthly review, has a large staff of paid organisers,

and conducts a planetary system of subsidiary organisations.

Its subsidy from the Comintern must run into tens of

thousands a year.

Vast numbers of the little leaflets

distributed at factory and dockyard gates, in the distressed areas, and

wherever trouble may be stirred up against the existing order of things, must

be a waste of paper, ink and Russian gold.

The British workingman, employed or

unemployed, is very conservative in his allegiance to law, order and tradition.

He hates the idea of Red Revolution, which he knows would make an awful mess.

In his inarticulate way he is intensely patriotic and won't stand for any

"monkey stuff" about the King, or the Army, or the Empire. When the

unemployed of Jarrow built a sports pavilion with

funds provided by Sir John Jarvis and his friends they asked for a large Union

Jack to wave from its flag-staff. Communist visitors in the distressed areas

get short shrift from men standing unemployed round disused pit heads. I marvel

why they are not more rebellious. Is it lack of spirit, or lack of

intelligence? I am inclined to think it is a shrewd common sense and that humour which makes them laugh when a paid agitator screams

wild words from a soap box. "'Ere, come off it!" they say. "Go 'ome and wash behind your ears." They are not tempted

to use their sticks of furniture—paid for on the hire system—as barricades.

They don't thirst for rivers of blood. They trudge off to the Labour Exchange to get their dole and hope that things will

take a turn for the better. They have turned a good deal lately and there are

more wages to spend. There is even money to save, judging from the latest

figures of the savings banks, which are astonishing. Our craftsmen and

mechanics and factory hands are getting higher wages than in any country in

The Young Communist League is recruiting

boys and girls in the slum districts, where Simon Tappertit

may still be found. "Up, and up, and up!" writes the enthusiastic

editor of Challenge. "Forty-five recruits this week; by the end of

January we shall have made at least zoo new members, in the first month of the

year. Actually this is not so very good. I mention it be-

IN

BLOODTHIRSTY

cause 100 of our best comrades are out there—in

These boys of the Young Communist League

are being stuffed with all the old slogans of Red Russia used by the

revolutionary leaders who are now mostly dead by orders of their comrade

Stalin. Capitalism must be destroyed. Religion is the opium of the people. The

workers must seize the means of production. The international class war must

overthrow the tyrannies of imperialistic nations. World revolution is the way

to world peace. Now they have new enemies, worse even than vested interests or

the demon of Capitalism. They are Fascism and Nazidom.

Hitler, Mussolini, and, in his little way, Sir Oswald Mosley—are recruiting

agents for the Communist party of Great Britain, especially perhaps among the

Jewish population, who have their own cause of hatred. Sir Stafford Cripps,

learned in the law, knighted by the King, and Mr

Maxton, of the Independent Labour party, have many

strange types among their followers—overgrown office boys who listen to those

orators on Tower Hill; undernourished students who economise

over lunch and wander up the Charing Cross Road to

read a flaming page or two in the Red bookshops; dreamers of utopias where all

will be rich and all will be happy; hollow-eyed shabby men with glib tongues

and shifty eyes who get paid by agents of the Third International; young

Irishmen who remember Tom Paine and "The Rights of Man"; Jewish

tailors who brood over the long story of persecution and pogroms; and youth

with revolt in its mind or the inferiority complex which seeks revenge by way

of Terror. There is also Professor Haldane. It's all

very interesting, but not, I think, alarming as a threat in this year of grace.

But if another world war comes even

But the red dream is still dreamed by

those who believe in fairy tales. It gets into the minds of young fellows over

here, not only in St John's College, Oxford, and some of the students at the

London School of Economics, but down by the London Docks in Bermondsey

and Poplar, in Hoxton and Houndsditch.

One hears its gospel preached on Tower Hill.

IX

The

Sowers of Dragons' Teeth

1

The Fatal Past

IS IT ANY GOOD looking into past

history—not long past—and retracing the fatal steps which, one by one, were trodden

by our leaders as though they were blindfolded or sleepwalkers on the edge of a

precipice?

Our present leaders, who, in most cases,

are our old leaders, resent any inquisition into events further back than

yesterday. They say: "Let the dead past bury its dead. We have to act

today. We ask you gentlemen of the House of Commons, and men and women of

Shall we let them get away with it quite

as easily as that? Isn't it necessary to look back a moment or two to find out

how it is that all the world is arming with feverish and frantic haste, and

that we are going to spend upon the instruments of war that vast sum of money which,

if it had been raised for social purposes—for the nation's well-being, health

and beauty—would have been a great advance in civilisation?

One could go back profitably for one's

mind as far as the Treaty of Versailles and those penalising

clauses which were designed to keep a great and dynamic people in bondage to

their enemies. There was no generosity of spirit which might have lifted

humanity out of the ruins of that time and created a comradeship and

co-operation between those who had fought each other.

We missed that chance.

We could—and perhaps should—re-examine

ourselves and indict our leaders—and those of France—for demanding from a

defeated nation unspecified tribute called reparations, rising to astronomical

figures which we knew, or should have known, could not be paid even by the

richest nation on earth, which at that time was the United States, and never

could be paid by Germany, exhausted and ruined after the war.

We might do well to remind ourselves that

out of the misery, humiliation and despair into which Germany was thrust by

these claims to reparations and the French invasion of the Ruhr—we had no share

in that—Hitler arose. As I wrote years ago, Poincare

was the father of Hitler. Our Foreign Office was the birthplace of General Goering.

But all that is rather boring. It is

always rather boring to look back at missed chances and wanderings down the

wrong roads.

Let us look at more recent history.

There was a Disarmament Conference in

It was not done.

Year after year those dreary and false

debates went on, about quantities and qualities, and every kind of technical

argument designed to waste time and prevent progress. That play actor Paul Boncour was a past master at this game. And our own

representatives at

It was our representative, Lord

Londonderry, who demanded reservations regarding aerial bombing when there

seemed some chance of agreement to prohibit that form of destruction. He has

denied this, but his words stand on the record.

It was our representative, Sir John

Simon, who, when the Germans were still in the League of Nations and pressing

for equality of arms on any low level which might be agreed upon—an equality

promised to them before the whole world—stood up and, with a glance at the

French delegates, announced that the new regime in Germany under Adolf Hitler had so altered the situation that he proposed

another period of probation for Germany—he suggested eight years—before they

would be allowed to have this equality in arms.

The German representatives saw that all

this was play acting, without sincerity, and without any intention of granting

actual equality in armed strength to the German nation.

We had missed another chance—the supreme

chance at that time—of delivering the European peoples from their overwhelming

burden of armaments and securing German co-operation in a system of law and

collective security which would have given some reasonable chance of peace to

Europe.

2

Hitler 0ffers Peace

When Hitler became chancellor and Führer of the German Reich he spoke more as a statesman and

less as a barnstormer. He seemed to forget certain passages in his book Mein Kampf, though

that was a best seller. He made before the German people and the world several

offers of peace, in words which were unequivocal, emotional and idealistic. He

was called a liar in the world Press.

He offered

Hitler offered to make a Western Pact

between

Hitler offered to limit the German army

to three hundred thousand men.

On

It was one of Hitler's

"surprises" which shocked the world and created more fear in

But when steel-helmeted soldiers with

guns and transport were riding through

It was as follows:

1. The German Government

declare themselves prepared to negotiate with

2. In order to restore

the inviolability and integrity of the frontiers of the West, the German

Government propose the conclusion of a non-aggression

pact between

3. The German Government

desire to invite

4. The German Government

are willing to include the Government of the

5. For the further

strengthening of these security arrangements between the Western Powers the

German Government are prepared to conclude an Air Pact, which shall be

designed, automatically and effectively, to prevent the danger of sudden attack

from the air.

6. The German Government

repeat their offer to conclude with States bordering

7. With the achievement

at last of

These proposals were of vast importance

to the peace of

There is no word of

The hostile critics of

But is it impossible for us, or France,

to understand the motives and the limit of

To the man in the street and the

third-class railway carriage in

I stood there listening at the open door

of the room in which the council of the League sat at a horseshoe table. Behind

me was a long corridor hung with tapestries. The eighth Henry had given his fat

hand to Anne Boleyn, his "truly beloved", as oft he wrote to her, and

led her down this passage to his banqueting room. The initials of that royal

pair are carved on the stone fireplace, not chipped off when Anne Boleyn's head

fell on the block and another lady took her place in the Court of St James's.

Long afterwards the second Charles, with his haggard face and dark eyes, had

walked up this corridor and stood laughing with his pretty ladies at the door against

which I leaned. The ghosts of English history crowded round me and I was more

aware of them for a minute or two than I was of the Americans, Italians,

Germans, Frenchmen, who stood close trying to get a glimpse into that room with

the horseshoe table where the delegates of many nations sat in judgment.

They condemned the action of Herr Hitler

in repudiating a treaty, freely signed by unilateral action. The Belgian

minister spoke with deep emotion, as though the Belgian people were again

threatened with invasion because German troops were on their frontier. Each

speaker spoke solemnly and sternly of this violation of international law. Herr

von Ribbentrop's defence

was ignored and dismissed. It was a painful time for

The verdict was inescapable. The German

government had broken the Treaty of Versailles in repudiating a clause without

discussion. It was—standing alone—another breakdown of international law and

another step to European anarchy.

There was no mention of Hitler's peace

offer nor of his hope of rebuilding the structure of

law now that he had regained the sovereign rights of

Mr Anthony Eden, acting with French advice—French

politicians were hot with passion—addressed a questionnaire to

On January 30 of this year—four years

after his appointment as chancellor of

In the course of his speech he announced

that the government would take over the control of the German railways and the Reichsbank as the final freeing of the state from the

provisions of the Treaty of Versailles.

"The Versailles Treaty is at an

end," he declared. "It took equality from our people and degraded us

to an inferior status. German honour has been

restored."

Then he made a promise which, if

believed—and it was not believed—would relieve the fear of his neighbours and remove the dark shadow which lies heavy over

Europe.

"With the achievement of equality

the time of so-called 'surprises' is at an end. As a nation possessing equal

rights

Was he lying when he said that? I for one

do not think so.

He declared that it was quite out of the

question to think of a conflict with

Was he lying? I do not believe that.

"I have already tried to bring about

a good understanding in Europe," he said, "and I have, especially, to

the British people and its government, given assurances of how ardently we wish